Steve Frankfurt

1983 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Advertising, Design, Illustration, Education, Typography

Stephen O. Frankfurt, initially overlooked in Hollywood, became the youngest president of Young & Rubicam Advertising by 1967. His innovative commercials transformed the role of art directors, emphasizing creativity and collaboration. After retiring at 40, he continued to influence advertising and film, leaving a lasting legacy in the industry.

Career

In the spring of 1953, Stephen O. Frankfurt went to Hollywood. He was 22 years of age and had three years of study at Pratt Institute behind him. He visited every major studio and ad agency in Tinseltown, and not one of them had any interest in either him or his talent. Fifteen years later his name earned international recognition when he was made president of Young & Rubicam Advertising, the youngest man in history to hold such office. Excluding a few industry giants, the art director was still a low man on the totem pole, sitting off in a corner somewhere while the writer or account executive would slip his instructions under the door. Frankfurt’s extraordinary new position gave art directors in ad agencies everywhere a remarkable lift. An art director had suddenly emerged as the head of the world’s second largest ad agency. How in the world had he come so far in so short a time?

Frankfurt admits that, unlike Palas Athene springing from the head of Zeus, he did not emerge fully developed into this dynamic and highly competitive world. As one of the first contributors to his career, he salutes James Cantwell at KNX, the CBS affiliate in Los Angeles. During the exploratory California trip, Cantwell assigned him to redesign the KNX logo and renewed the assignment week after week. Furthermore, Cantwell put him in touch with the blossoming UPA studio, which made a tentative job offer. A tempting scholarship offer from Pratt and Cantwell’s sage advice sent him back to New York. After assuming the presidency of Y&R, Frankfurt learned that the work at KNX had been created solely from the goodness of Cantwell’s heart. This was an example well taken, and since then Frankfurt has done much to further the careers of others who followed him.

After his graduation from Pratt, Frankfurt worked at UPA-New York. A painter of backgrounds and the youngest man there, he lost the job because he could not keep up with the pace of work at the busiest studio in town. But he now had experience in animation and camera techniques and had proved his innate talents. Frankfurt was far ahead of most in the ad agencies in this regard. The people handling TV were, in the main, former movie production types and radio writers imported from Hollywood because they knew the difference between such esoteric terms as voice-over and lip-sync.

Frankfurt had earned introduction to Y&R as a shuttler of film cans between studio and ad agency and the vastness and formality of the art department intimidated him at first. Nevertheless, he accepted the offer by Jack Anthony and Jack Sidebothom to be an assistant art director in their fledgling IV department. In 1957 he was made TV art supervisor and a producer, an enviable position because he could now follow his concepts through to completion. While a producer, his trend-setting commercials helped to break down the barriers of title that had kept art directors far removed from the production process, and by the mid-60’s, the art director-producer would be a familiar figure.

For Bufferin, a human eye, a watch, and a package with the sound of a beating heart over it represented, in the words of one journalist, “the only analgesic commercial not to give you a headache. “The 60-Second Modern Drug for Pain” was shown during the televised Johanson-Patterson championship fight and the contrast between the hushed tones of the sport and the frenzied business in the ring at Madison Square Garden added to the impact of a commercial that pioneered the way to many new approaches in the genre. For Johnson & Johnson baby powder, the camera used close-ups, “looking at the baby as the mother would. A Modess commercial subsequently selected for the permanent film collection in the Museum of Modern Art started as an abstract modern art piece and became, in full viewing, a portrait of elegance and understated salesmanship. None was more influential in creating the era of the “art directed commercial” than the Eastern Airlines Whisperjet” campaign in which birds in flight and the alluring voice of Alexander Scourby combined to present the intangible “wonder of flying. ”Television in those days was a toy,” comments Frankfurt today. We had creative freedom.”

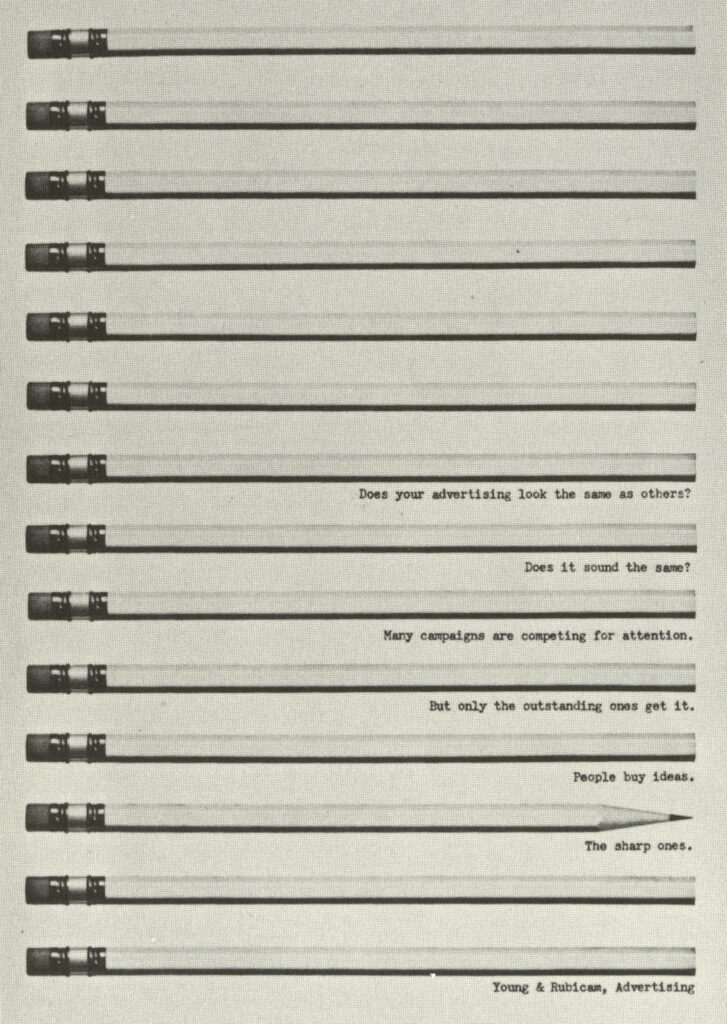

Frankfurt says he was molded by his teacher,Alexey Brodovitch, whose passion for new visual idioms changed the thinking of an entire generation of young art directors. Frankfurt adopted Y & R’s early motto, ”resist the usual,” as his own, and feature film directors from the United States and abroad soon began saying that the best work in film could be seen nightly on the American TV tube.

On one spot he used no voices at all. On another, he used the voices of real children instead of those of actresses who had done the work previously. He approached sound as a visual, with color. The act of pulling the string of a Band-Aid, and that of paper ripping, were transferred to film as recognizable human experiences. Frankfurt lavished both attention and money on his commercials and he brought in only the best talent. He asked Irving Penn to shoot his Johnson & Johnson commercials. He usedHoward Zieff‘s comedic sense to great advantage. Bill Helburn was recruited from print to create high fashion Tek Hughes toothpaste commercials. Innovation was highly prized. For Sanka be produced a spot with a piece of string in stop-motion as the commercial’s spokesman. This won a Venice Film Festival Award. A stroboscopic techniquea series of recurring images of double exposures akin to Duchamps ”Nude Descending the Staircase”was the technique for another Band-Aid commercial. A spot for the Cigar Industry was so effective that pressure mounted to take it off the air: it employed the first application of slow motion in reverse to show cigarette smoke as it traveled through the lungs. Frankfurt was taking risks. Irving Penn explained it this way: “He has always been a rarity in the advertising business. He believes that magic can happen in the film studio…and keeps his commitment to the client as loose as possible so as to make good use of a miracle should it happen.”

As a result of efforts like these, Frankfurt was put in charge of the entire art department at Y&R. Searching for a way to communicate his ideas to the staff, he went toBill Bernbach,George Lois,Arnold Vargaand others and asked to borrow some of their proofs. In a hallway of Y&R’s art department, he created a gallery of works that he most admired. He informed the members of his department that within a year he wanted to replace these examples with ads of comparable or superior merit created in their own department. It took two years.

During this revolutionary period, not a single individual was fired. Providing the right climate is, Frankfurt states unequivocally, “almost as important as the talents you bring to the job.” Writer and long-time associate Sylvia Simmons recalls how the staff sat in line on the floor while waiting to present their work. “Steve has this great visionary sense and would take a good concept and then add something to it. “TV directorBob Giraldi, an assistant art director at that time, calls Frankfurt “the most significant and forceful influence” on his career.

One of the first to follow the Bernbach example, Frankfurt formed writer and art director teams. If the chemistry of the mix didn’t work, he had faith enough in the talent of his people to try other team combinations. The experimentations with staff and the uplifting campaigns were successful enough for him to be named president of the agency in 1967.

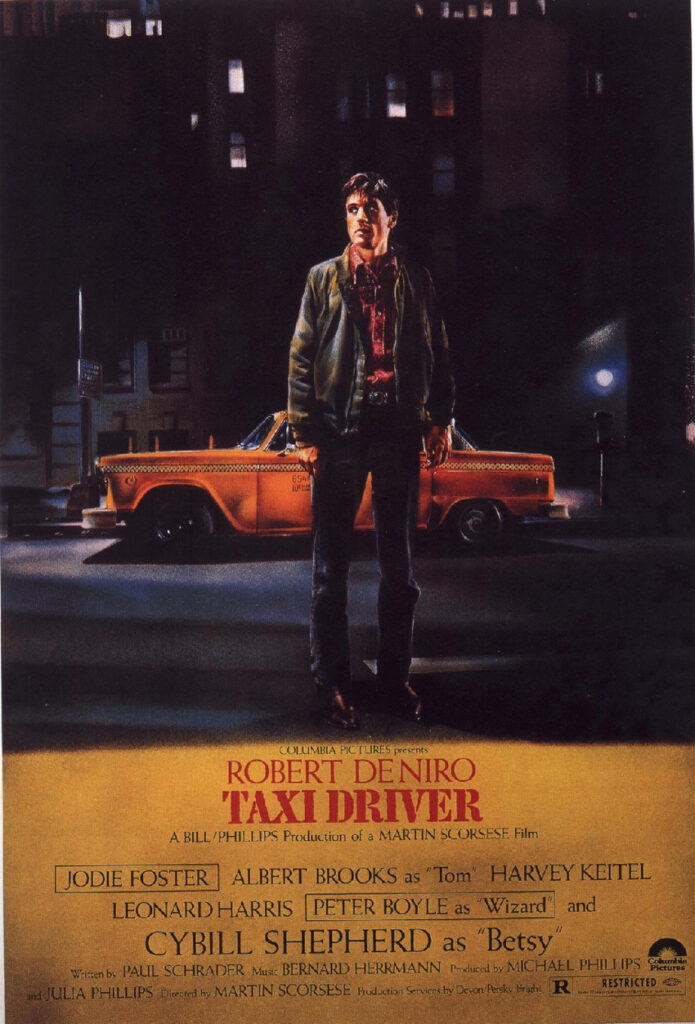

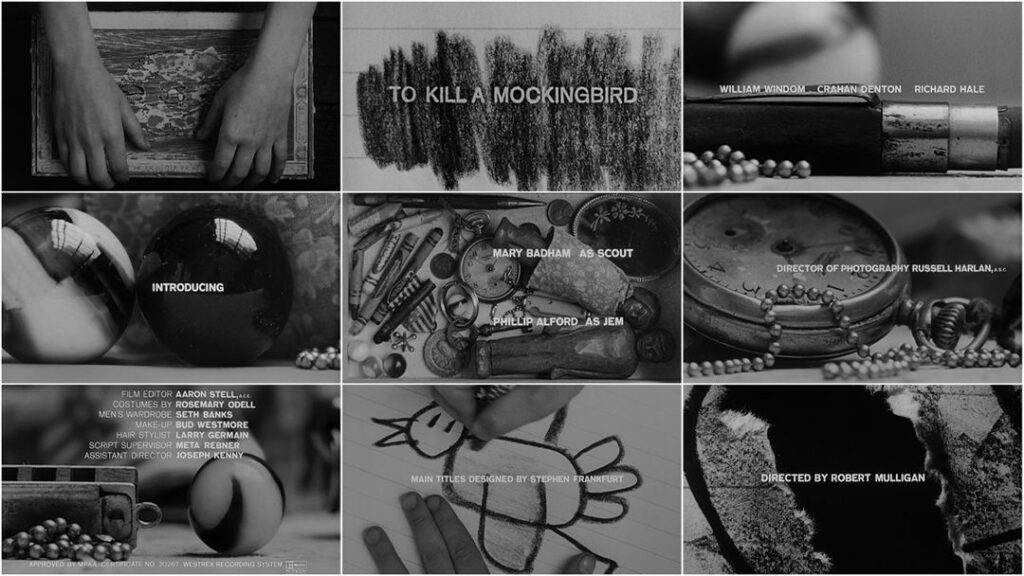

Though born and raised in the Bronx, the Hollywood connection somehow always seemed to be in the background, and in the early 1960’s he got a call from producer Alan J. Pakula, who admired his commercials. Pakula asked him to try his hand at the main titles for “To Kill A Mockingbird. Frankfurt worked closely with sound expert Tony Schwartz, his associate on many commercials. TheShow Magazinecritic led off his review of the film with the observation that “the titles that adorn To Kill A Mockingbird’ are about as striking as anything…yet devised. Later when Charles Bludhorn of Gulf & Western’s Paramount presented him with the “Rosemary’s Baby” project, Frankfurt’s cinema scope was greatly enlarged as he directed the entire campaigntitles and trailer, posters and all media advertising. ”Hollywood said we were breaking all the rules,” Frankfurt points out now, “and I explained that was my aim precisely. For “Rosemary’s Baby, essentially a horror film, Frankfurt decided that the most startling way to surprise his audience was by not showing the baby but by hearing it and superimposing an empty baby carriage on Mia Farrow’s face. The copy says simply: “Pray for Rosemary’s Baby. Since then he has been associated with such eminently successful feature productions as “Goodbye, Columbus,” “Arthur,” “Emmanuelle,” “Superman,” “All That Jazz, “Kramer vs. Kramer,” “Sophie’s Choice,” and “That’s Entertainment, totaling more than 55 in all.

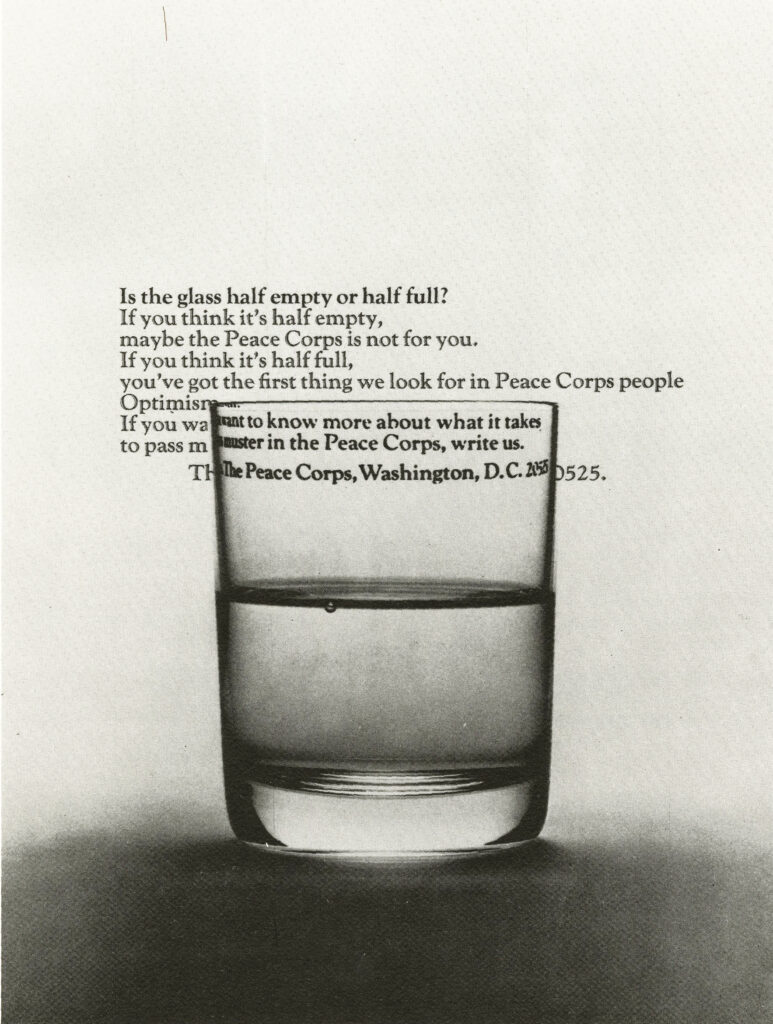

Leadership frequently consists not only of what one does, but also of what one inspires others to do. The massive conscience-examining period of the 60’s saw many agencies involved in the public service area, and none more so than Y&R, whose campaigns, many of them award-winners, were for the Peace Corps, The President’s Committee on Mental Retardation, JOBS, N.Y.C., and the Urban Coalition (“Give a Damn”). Frankfurt had a guiding hand in these.

He retired at 40. “I never had a frustrating day in that company,” he later explained, “until I became president. Frustration behind him, Frankfurt Communications came into existence in 1971, established first in the Time-Life headquarters where he acted as special consultant to chairman Andrew Heiskell. He also became active working with the Children’s Television Workshop, producers of “Sesame Street. The firm later became a division of Mattel, Inc. and he found himself involved in such diverse enterprises as the Ringling Brothers Circus, a ski resort in Utah and the preservation, on film, of African wildlife. But he had grown up in a large company, Y&R, so it was “the most natural thing in the world to join Kenyon & Eckhardt when it was proposed to him,” he says today.

At K&E he is president of Frankfurt Communications, a subsidiary, and chief creative officer of the agency, on the one hand dealing primarily with film and book projects for Warner Communications and other clients, while on the other playing a contributory role in everything produced on the advertising side.

Frankfurt has also given much time and energy to such organizations as the New York City Center of Music & Drama, where he is on the board of trustees, the American Film Institute, where he has served on the board of trustees, Pratt Institute, where he has been a board member, and New York University School of the Arts, where he is on the advisory council.

Frankfurts ability to see things with fresh, enthusiastic eyes is an attribute cited by everyone with whom he has been associated with over the years. Tony Schwartz says that he thinks in much broader terms than the average person. Time correspondent Richard Clurman, comments that Frankfurt has 12 ideas on any subject, 10 of them that no one should have thought of, and two that arebrilliant.

He is a man who admits that he thinks with his heart rather than his head. The magical bridge to creativity, he insists, lies in the appreciation of the value of surprise. “To find a way to make that surprise work, to interrupt, if you will, and get impact. In the final analysis, somebody has to take something and see it differently or say it differently.”

As Frankfurt enters the Art Directors’ Hall of Fame, it is no surprise that Hollywood now comes to him. And it will come as no surprise to anyone in the years to come that he will go on innovating, sometimes attempting the unthinkable, sometimes attaining it.