Sam Scali

1984 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Advertising, Design, Typography, Education

Sam Scali, founder of Scali, McCabe, aimed to create the best ad agency globally. Renowned for his creativity and attention to detail, he emphasized the importance of listening in advertising. His notable campaigns include Perdue Chickens and Sperry Corporation, showcasing his innovative approach and commitment to excellence in advertising.

Career

In 1968, a year after Scali, McCabe was founded, Sam Scali was asked what his goals were. His answer was unequivocal: “To be the best ad agency in the world.” Millions of dollars in billings later and with much acclaim for creativity bestowed on the agency from all sides of the communications industry, if asked of his goals today, he still says he ”wants to have the best ad agency in the world. We work at it every day.”

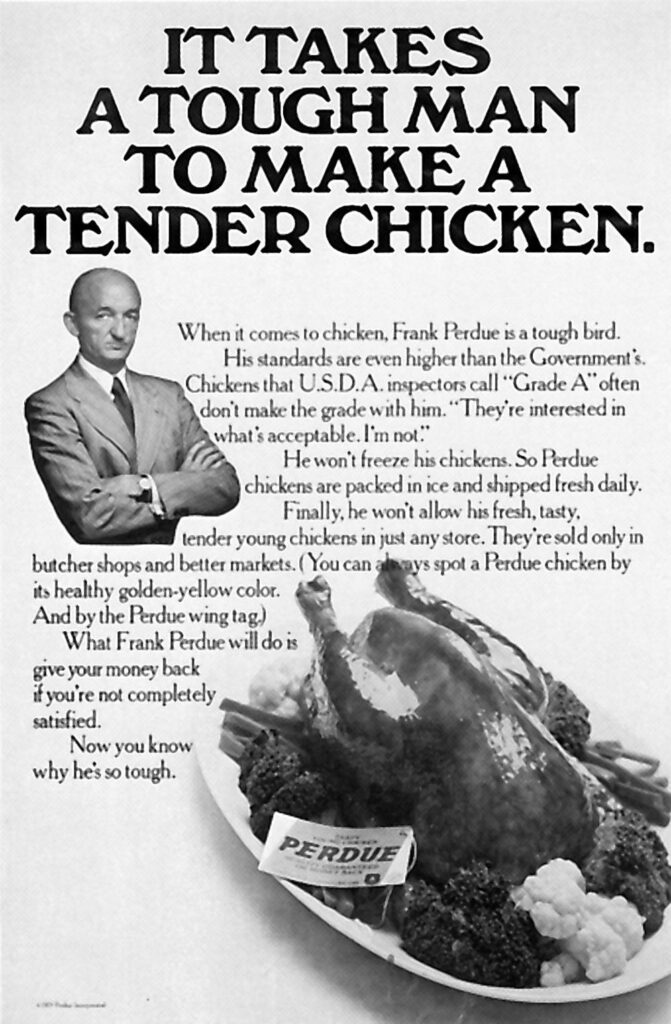

When other people view the agency’s reel, more often than not they cheer, nod in agreement, laugh or applaud, while Scali is likely to remain pensive and expressionless. “The work is good, but it can always get better,” says Scali, a severe self-critic. Scali is the complete advertising professional; there is nothing in life that pleases him so much as poring over the type books he has studied a dozen times before to uncover the gem of a type for a new campaign. Small details delight him. The face selected for Perdue Chickens was “picked for a specific reason. If you look closely at the inside of the O’s, they look like eggs.” His attention to every detaillayouts, handling of photography as well as judgments on the big ideais legendary in the agency that bears his name.

One of the campaigns of which he is proudest was created for Sperry Corporation. Sperry had been spending money for years without a great deal of success with its image. One of their salesmen revealed off-handedly that their people had to listen harder when trying to land a client because they were cast in the underdog’s role. The concept of listening became Sperry’s corporate charge and Scali was instrumental in planning a program which involved having the client’s employees trained in becoming better listeners. Scali’s moving and dramatic ads revealed the unresolved issues that confront people who do not listen. What made it meaningful to him is that the ad effort did not merely confront company problems, but human problems as well, and positioned to alter Sperry’s image, they then sold hardware.

Says writer-partnerEd McCabeof Scali’s sensibilities: “He has a soundness of judgment about concepts that is almost infallible. We call it the ‘Sam Test’. If you are pursuing a direction and he agrees with it, you know you’re on very solid ground.”

When Scali was a teenager, “all he ever wanted out of life was $100 a week and to enjoy what he was doing. He attended the School of Industrial Arts, now the High School of Art and Design, and then went to work at Photo Lettering, spacing type and headlines, but since he “didn’t know anything about type, he decided to learn. Scali was always more resourceful and more full of ideas than the pack.Aaron Burnstaught Scali in his Advanced and Experimental Typographic Design class at Pratt. “Sam would bring in solutions to design problems,” recalls Burns, “that made us all, teacher and fellow students, stop and look with admiration at his exceptional creativity. Sam didn’t stop with just one solution to a problem. He would do several and each seemed to be better than the other.”

In his next job, with a direct response agency, Scali was engaged in doing mechanicals and small drawings, always with an eye to bettering his lot. As a result, today he is responsive to young people who are impatient to get ahead and sees every portfolio that is dropped off for him because he remembers vividly “how impatient I was when I had so much to learn.”

His status improved at his third post, working with Ben Rosen and Herb Koons. They became two mentors who allowed him to freelance as a designer with anything he could get his hands on. This marked the one occasion when he was fired. Rosen said he was getting “too comfortable.” That very day he was hired by the Harry Zelinko Studio, where he worked for two years, and next joined Sudler & Hennessey, where he says he was “lucky enough to get a job as a junior art director in the bullpen. The creative department then includedHerb Lubalin,George Lois, and writer Fred Papert. When Lois went to Doyle Dane Bernbach and a spot opened up in the sales promotion department there, Scali didn’t hesitate. He liked his sales promotion job well enough but greatly wanted to work on consumer accounts at DDB and would drop off his ads every day in the office ofBob Gage, who eventually broke down under the weight of the indisputable evidence of Scali’s meritorious creative performances.

Up to now in the agency business, design ingenuity, rather than concept, was the hallmark of the best advertising. Scali had managed to be employed by two agencies that would change this, Sudler and DDB. Now in the late 50s, Lois, Papert and Julian Koenig started their trend-setting Papert, Koenig and Lois agency and Scali came on board. An industry reporter called the agency “the Stillman’s East of the advertising agencies,” and it was an exciting place to work. Scali’s break came with the Xerox account and the concept of taking office equipment out of the office and dealing with it on personal terms. Who else but Scali would have conceived, when copying machines were a novelty, of having a three-year old child demonstrate the miracles of Xerox? Scali’s ideas about advertising took root here. Design wasn’t enough. Big ideas weren’t the whole story. Research was necessary. And equally important to the equation was the right media. They ran TV for theHerald Tribuneon the nightly news, breaking with their own news headlines for the following day. It was the first time a newspaper had sponsored a television news program. They heralded the fact that “a great newspaper didn’t have to be dull.”

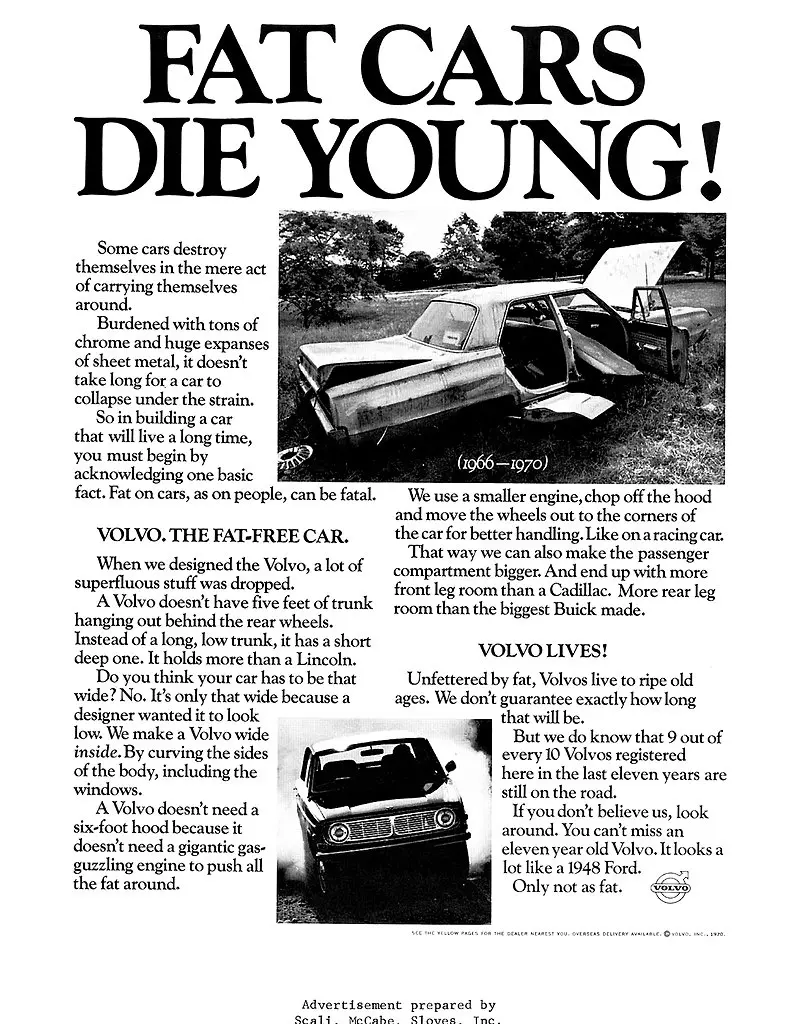

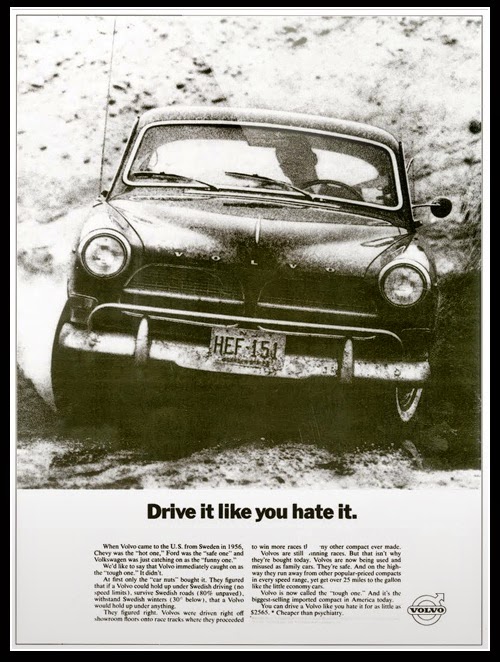

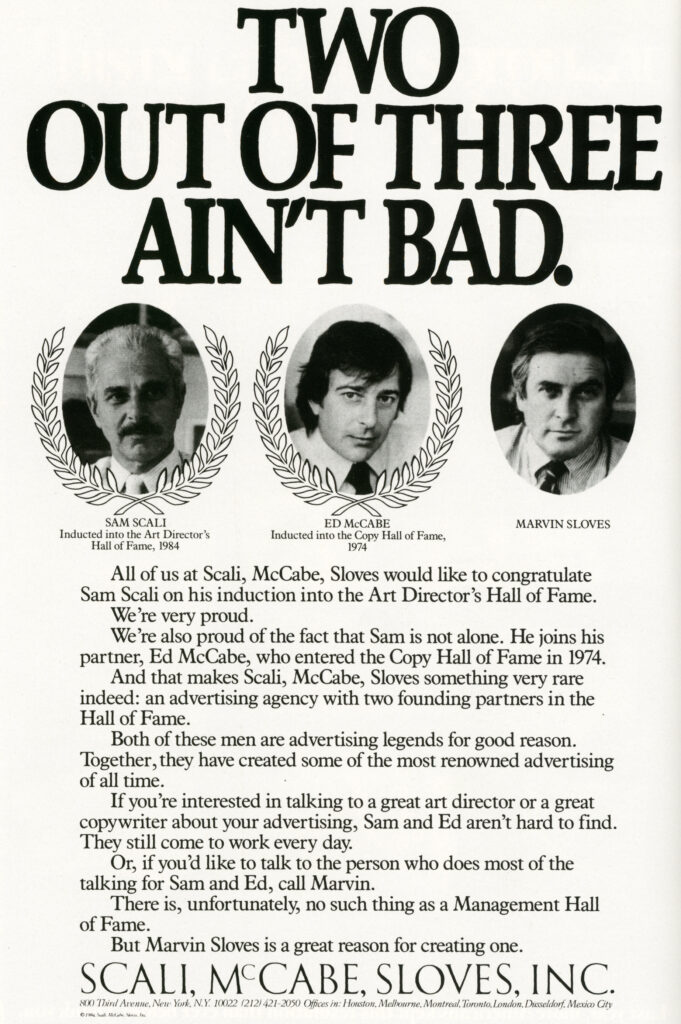

Scali, McCabe, Sloves, Inc. was founded by five partners, four of whom came from PKL in 1967. They wanted to create an agency where marketing, media, research and creative shared the spotlight in a full-service, no-nonsense ad agency. Alan Pesky, Marvin Sloves and Len Hultgren asked Scali to recommend an art director. He recommended himself. Soon after, Scali called Carl Ally, Inc. to ask Ed McCabe to recommend a writer. McCabe recommended himself. They started out with no billings but quickly picked up Volvo and a host of accounts. Perhaps their most famous campaign has been for Perdue Chickens, for whom they developed an entire new category. Scali’s direct, no-frills visuals and innate humor with McCabe’s copy have made Perdue a household word in America and have brought presidents from companies all over asking for stardom, all of whom have been refused because it made no marketing sense for them.

Scali believes in creating hard-hitting ads that directly pursue the competition at its weakest point. In spite of his many awards, he refuses to glorify advertising’s contribution to society, or his own, out of proportionor to put it in any other frame of reference other than a business he loves. “We shouldn’t overreact or put what we do out of perspective,” says Scali. It is this balanced judgment, combined with unwavering standards, that has made him one of the best advertising teachers in the field.

It has been observed many times by his peers that Scali is a very nice, quiet guy who is almost unflappable. Inside that quiet exterior, however, resides a raging fire of creativity that catches people off guard with its simplicity, directness, and brilliance.