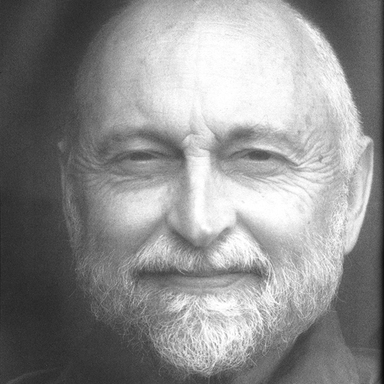

Roy Kuhlman

1995 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Design, Illustration, Advertising, Education, Photography

Roy Kuhlman, an aspiring artist turned designer, studied at prestigious art institutions before finding his niche in graphic design. He worked with notable figures in the industry, created innovative designs for Columbia Records and Grove Press, and was influenced by Abstract Expressionism, ultimately shaping his unique graphic language.

Career

Pursuing his childhood dream to become the next Rembrandt, Roy Kuhlman studied at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles and, after moving to New York in 1946, the Art Students League. After a number of years, however, he realized he was looking for something else. This he found when he ran into Arnie Copeland, a friend from California who had just become art director at Lockwood studios. Copeland introduced Kuhlman to Lockwoods bullpen as a troubleshooter and paste-up expert. Knowing practically nothing, except on which side to smear the rubber cement, Khulman proved a quick study and soon lived up to his presumed reputation. At night he taught a basic design course at the School of Advertising and Editorial Art, alongside such professionals as Eugene Carlin andJerome Snyder.

Another big break came for Kuhlman when he was offered a job at Sudler & Hennessy, where he worked with Carl Fischer, Art Ludwig, and Ernie Smith, as well as the consummate designer and teacherHerb Lubalin. In 1954, Neil Fujita asked him to take over his position at Columbia Records. There, he gradually pooled a staff of young designers such asIvan Chermayeffand Al Zalon, producing some of the periods most innovative work.

One year later, Kuhlman was hired by Ruder and Finn to establish an in-house art department. The budget was low and the graphic pieces sent out were small in number. Kuhlman worked with Ed Brodsky, and together they began to gain recognition until Kuhlman felt it was time to move on and try his hand at something new.

Having decided to go out on his own, Kuhlman rented a studio above Fischers, on East 54th Street. Influenced by his friends photographic skills, Kuhlman began solving design challenges with photography. This led to an introduction to Bill Buckley at Benton & Bowles, who gave Kuhlman the most challenging assignment of his career up to that timethe famous IBM series Mathematics Serving Man, which won the AIGA Best Ads of the Year Award in 1958.

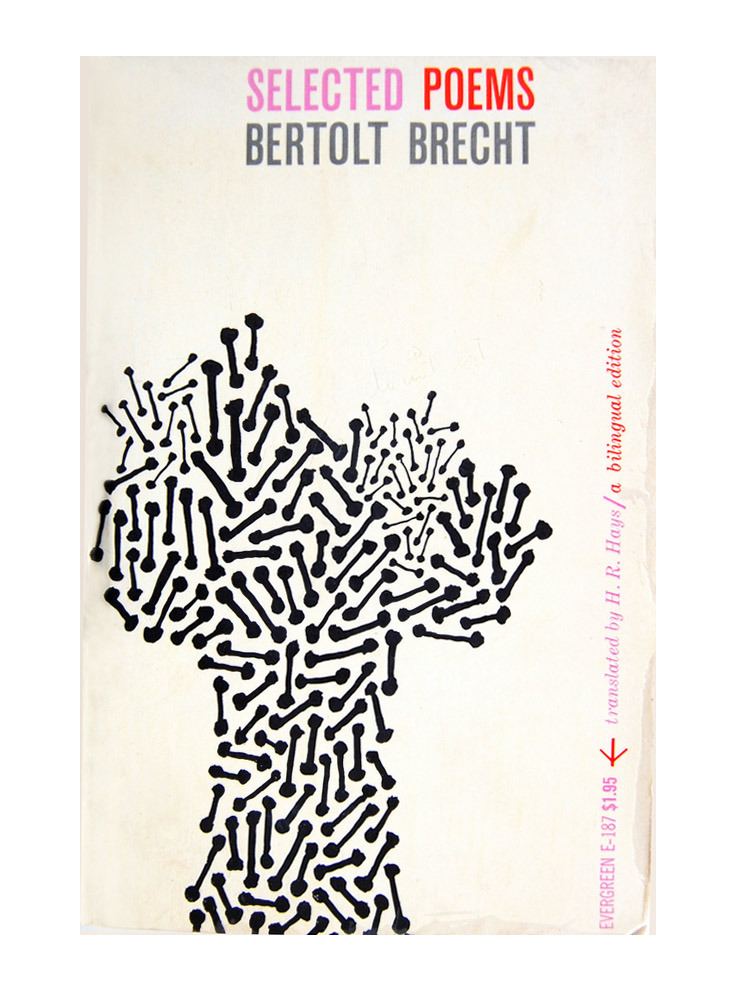

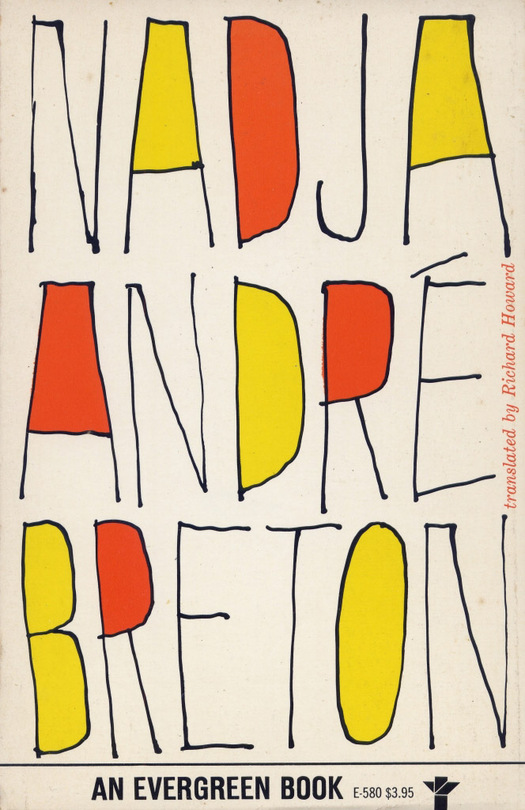

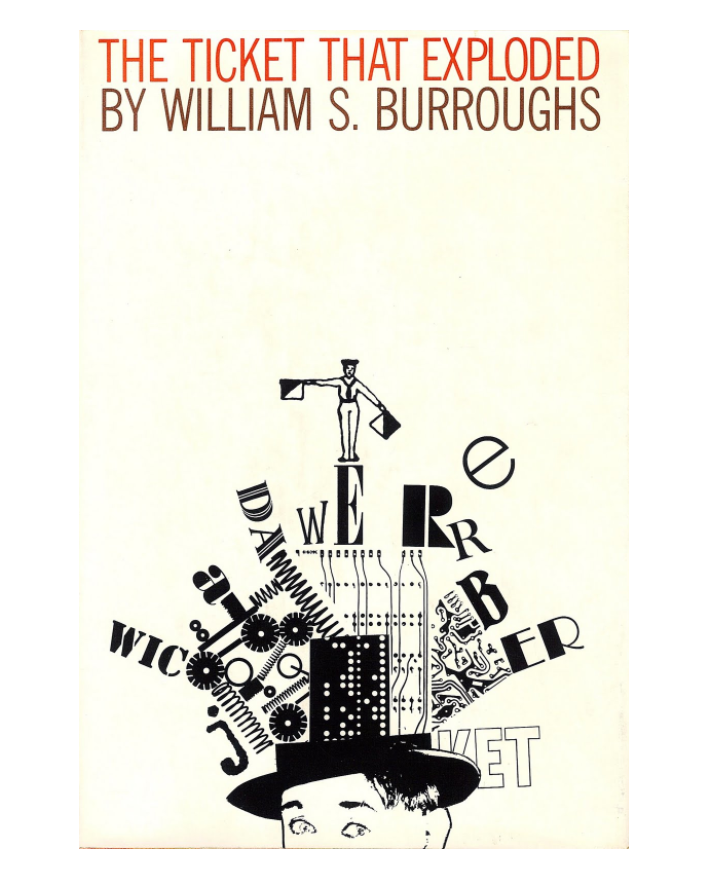

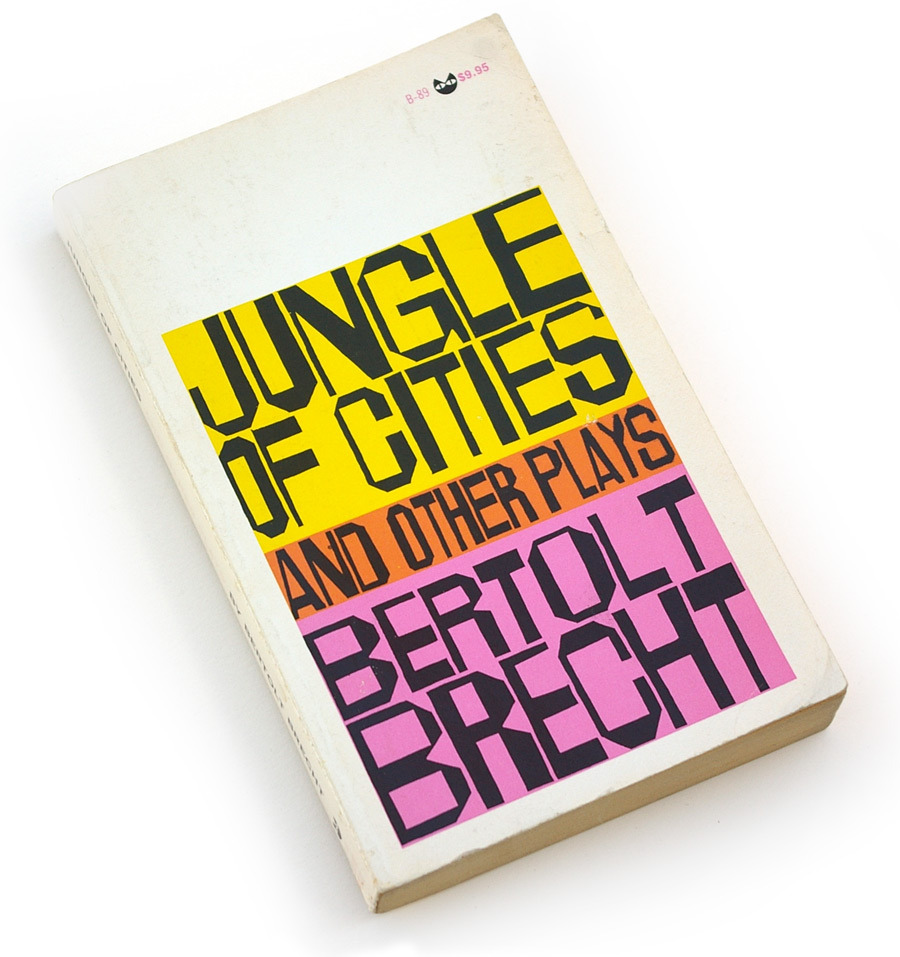

Although Kuhlman citesAlvin LustigandPaul Randas influences, it was the Abstract Expressionists, particularly the strong, simple style of Franz Kline, that truly inspired him. Kuhlman was one of the first to apply Abstract Expressionist ideas to design. His approach was loose, spontaneous, and serendipitous, and he worked quickly and instinctively. Because he felt there was a loss of quality if art was resized, he prepared comps in the same size as the final mechanical. Kuhlman developed a graphic language of his own, and anything within reach became part of the developing visual pastiche: old engravings, the insides of bank envelopes, his own photography, photograms, Zipatone sheets and collages, and odd pieces of letterpress type left over from other jobs.

In 1962, Kuhlman entered the movie industry. His film colleagues at Elektra Films, Jack Goodford and Lee Savage, described him as the first film primitive. After two years, he returned to motionless graphics, as creative director in charge of corporate literature and sales promotion at U.S. Plywood, where he remained for almost five years. Then, on a recommendation from Kuhlmans friendHenry Wolf, IBM invited Kuhlman to create an educational seminar on the concepts and technologies behind the development and the future of the computer. In three years, he produced 700 slides and 52 live-action and animated 35-mm shorts. After this challenge, Kuhlman decided to concentrate on special effects for film animation. Just as he completed his sample reel, video special-effects generators made his newly acquired skills redundant, and he chose to retire. In this business, if you have a ten-year life span, youre luckymine lasted 35 years.

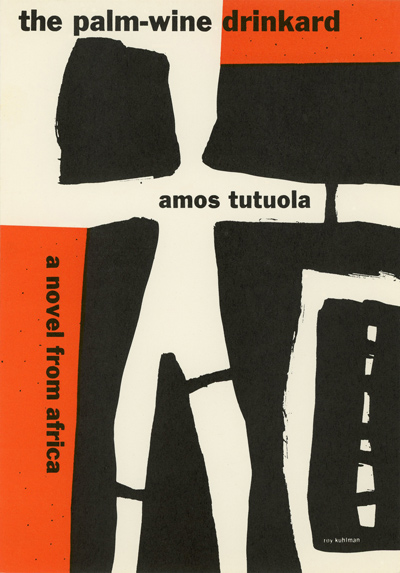

One of Kuhlmans fondest memories of his career took place in 1951, in a small Greenwich Village office of Grove Press, the fledgling publishing company that eventually brought to national prominence the writers, art, and artists of the avant-garde. He showed his portfolio of illustrations and comps, mostly bad black-and-white photos, clumsy type, mostly sans-serif, to publisher Barney Rosset, who was not impressed. Just as Kuhlman was about to close the portfolio, Rosset caught a glimpse of doodles Kuhlman had been planning to show to record companies. When Rosset, who numbered among his friends Willem de Kooning, Kline, and Jackson Pollock, saw them, he said emphatically, This is what I want.

For the next twenty years, Kuhlman produced some of his most brilliant work for Grove Press. His designs were the perfect counterpoint to the texts Rosset was publishing.Story of O, the erotic novel by Henry Miller, for example, was packaged in a plain white jacket to camouflage what was inside. After Grovethe first to publish third-world titles in the United Statesbegan publishing foreign titles in 1966, Kuhlman produced such covers asThe Brave African Huntressby Amos Tutuola andThe No Plays of Japanby Arthur Waley, which demonstrate his ability to reach both conceptual and abstract solutions. Rosset rejected only a few cover ideas. I usually had five seconds to get a yes or no from Rosset. So, I walked slowly across the office toward Rossets desk, holding the comp up so hed have some [extra] time to look at it, Kuhlman says, adding, Barney was the greatest client I ever had. He gave me the freedom to explore, to fail, and to win.

Please note: Content of biography is presented here as it was published in 1995.