Robert Gage

1972 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Advertising, Design, Illustration, Photography, Education

Doyle Dane Bernbach revolutionized advertising in the 1950s by promoting products through relatable human truths rather than statistics. Co-founders William Bernbach and Bob Gage emphasized creativity and intuition, leading to memorable campaigns. Gage's innovative approach and sensitivity to human emotion established enduring standards in advertising.

Career

It is widely agreed that the advertising agency of Doyle Dane Bernbach was the primary force in changing the face and direction of contemporary advertising. The agency precipitated this revolution on the threshold of the fifties by introducing the refreshingly simple concept that a product can be promoted more gainfully if its advertising is predicated on a believable human truth, artfully designed and cogently presented. Prior to the fresh DDB breeze, the advertising community had heavily relied on statistical research and arch techniques of graphic design as basic methods for capturing the public attention. These past twenty or so years have more than confirmed the clear-sightedness of what is now referred to as the Doyle Dane Bernbach approach. Although the agency has grown and prospered, it appears not to have lost one erg of its youthful energy and enthusiasm. As a result of its pervasive influence, many of its advertising slogans have been absorbed into the popular vocabulary and the imagery of its campaigns have entered the popular culture.

The vision of a “new advertising” was largely the construct ofWilliam Bernbachwhile he was the creative director of Grey Advertising Agency. By good fortune, Robert Gage, an art director at the same agency, held kindred views and joined Bernbach as a colleague-in-arms when DDB was launched in 1949. Bernbach and Gage provided an amalgam of concept, artistry, and sophisticated intuition that was new to the field. In an address to the Art Directors Club more than a decade after the formation of Doyle Dane Bernbach, Bernbach summarized the agency’s credo: “It is our belief that there is nothing more practical to an advertiser than an intuition so refined by practice that it can provoke a reader to attention with fresh, imaginative insight, or if you will, ideas. It is our belief that every other activity in our business is a prelude, however important, but just a prelude to the final performance that is the ad, and that the measure of that performance is its persuasion, and that persuasion is not a science easily learned like an equation, but an art that can reach inspired heights only by a deeply personal intuition.”

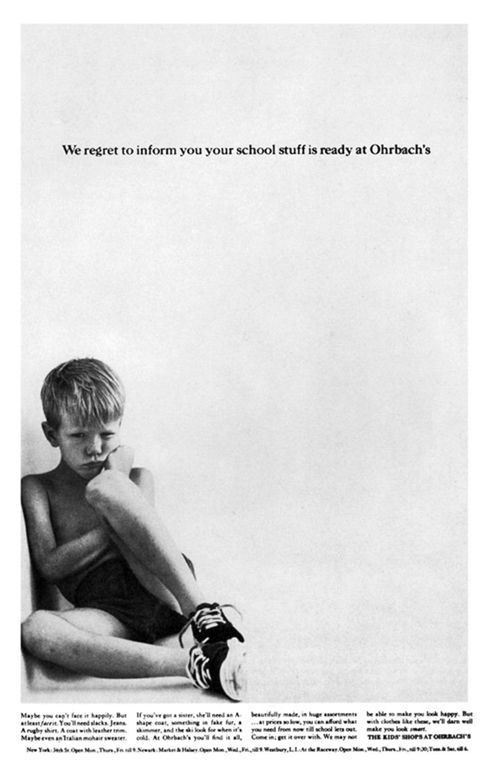

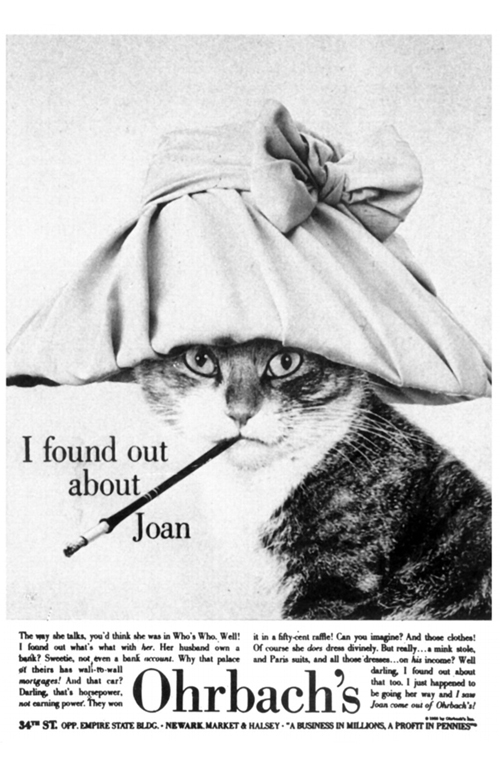

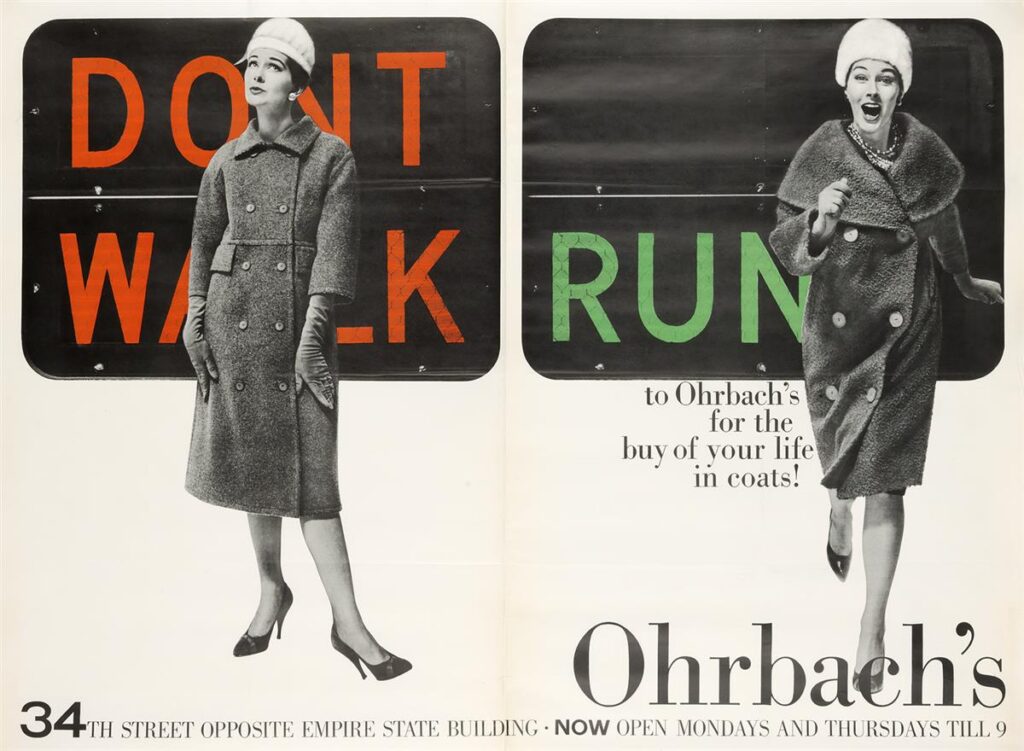

By the sternest measure of performance, Bob Gage has been the most glorious of persuaders. A short biographical note written by Gage, after some thirteen years of inestimable accomplishment, says succinctly: “Bob Gage, Vice President and head Art Director of Doyle Dane Bernbach since the day it opened its doors.” The statement, so spare yet so pithy, tells us something of Gage’s modesty, his straightforwardness, and his keen sense of economy. His exceptional creativity he leaves for others to comment upon. One hastens to add that from “the day it opened its doors,” Doyle Dane Bernbach, with Gage in its artistic forefront, has fulfilled the promise of its first hopeful vision many times over. Gage’s first major foray for the young agency was the campaign for Ohrbach’s high-fashion minded store with a policy of low popular prices. It was a seed campaign Bernbach and Gage had inherited from Grey because of their work on it there. It was also the first demonstration of the innovative writer/art director dialogue. In one swift stroke, the age-old and artificial separation between copy and design was dissolved. While it took a number of ads to shed some of the typographic affectations of previous Ohrbachs campaigns, sprightly word and image plays presented in endlessly inventive ways the Ohrbach leitmotif of top fashions at bargain prices. Gage’s ability to put an idea in direct, captivatingly human terms was exemplified in each successive ad. The series reached its quintessential climax in 1958 with a design form that placed an unadorned large photograph in separate but equal relationship with the copy. This form became a hallmark of the agency and has been imitated by the countless epigones in the advertising field. The brilliant case in point is the ad that depicts a haughtily attired feline, complete with cigarette holder, symbolizing a snobbish female who, as the copy cattily and chattily tells us, is envious that her lower status neighbor gets her queenly clothing at Ohrbach’s. Gage brought a sort of “Occam’s Razor” approach to advertising.

Alluding to his method, he said: “We never resort to visual tricks to attract a reader’s attention. Our creative solution is derived directly from cold facts about the product itself. This is fundamental to Doyle Dane Bernbach.” Gage, of course, was again too retiring to say that cold facts would remain ever inert without an inspired intuition to transmute them into a hot advertising concept.

With the Ohrbach’s campaign and its attendant commercial success as a debut, Doyle Dane Bernbach, as well as Bob Gage, attracted rapid attention from both peers and clients. A diverse range of advertising problems afforded Gage broad creative scope and opportunities for greater personal insight. Where one product required wit and levity to make the realm of bargain hunting a fanciful amusing adventure, other campaigns brought out what many feel is Gage’s most ingratiating qualitynamely, his abiding humanism. “Bob Gage has the capacity to make you feel,” Bernbach says, and that sensitivity to people, the ability to convey in a few strokes the expanse of human emotion, is revealed in the campaigns for Jamaica tourism and the Polaroid camera. Again, no trickssimply an intuitive, perceptive grasp of the essence and even the nuances of what will enthrall the reader. The tourism series, with its bold type stretching beyond the boundaries of the page and its photographic romance with the richly hued island and its warm vivacious people, makes the city dweller virtually smell the intoxicating fragrance of escape. The Polaroid series, by sharply reducing the words and expanding the picture, tells everyman he has a modern magic in his hands that can capture life’s wondrous moments foreveras if little people were bigger than life itself.

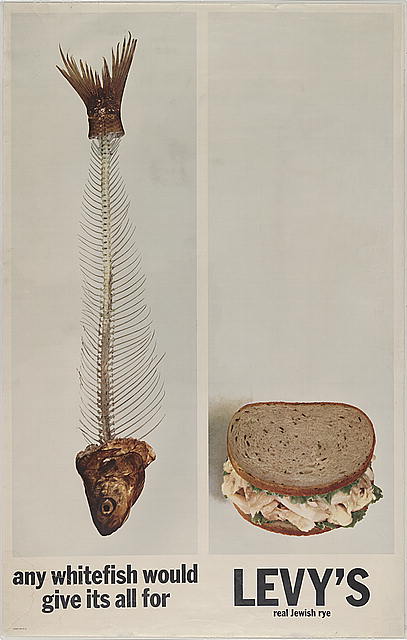

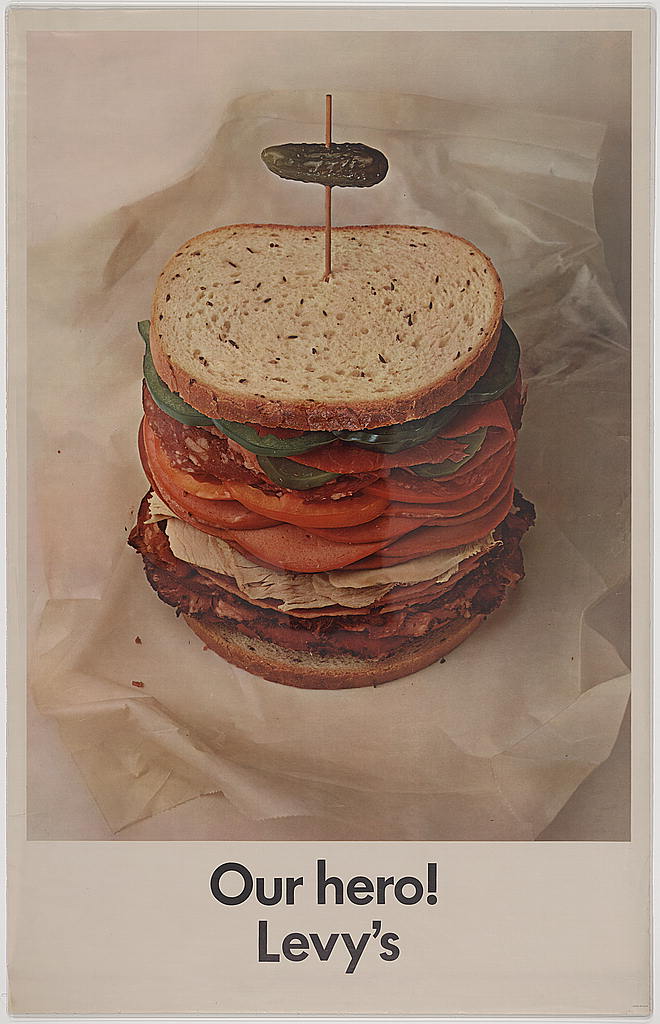

Because Gage is so persuasive and his creative mechanics so well concealed, there is a tendency not to pay full tribute to him. One need only remember the Levy’s bread series to see that Gage was, in that campaign, pointing the way for pop art. Because Gage eschews flamboyance, one can only savor the subtle invention of his exquisitely devised pages.Helmut Krone, a Doyle Dane Bernbach colleague and a distinguished art director in his own right, speaks glowingly of Gage as a designer: “Whatever you think of in terms of page design, he has been there. One may fail to notice his contributions because he doesn’t linger with any of his discoveries. He is a restless adventurer.” Phyllis Robinson, one of the profession’s most prominent copywriters and a collaborator with Gage on many campaigns dating back to Doyle Dane Bernbach’s first days, commented on Gage’s endless concern with detail, particularly the appropriateness of the copy: “Is it good enough?” “Is it surprising?” “Has someone done it before?” “Have we done it before?” Doubtless, this challenging self-search reflects Gage’s study with Brodovitch at one of his famous design laboratories, where Brodovitch continually impressed his students with the desire to do that which had not been done before.

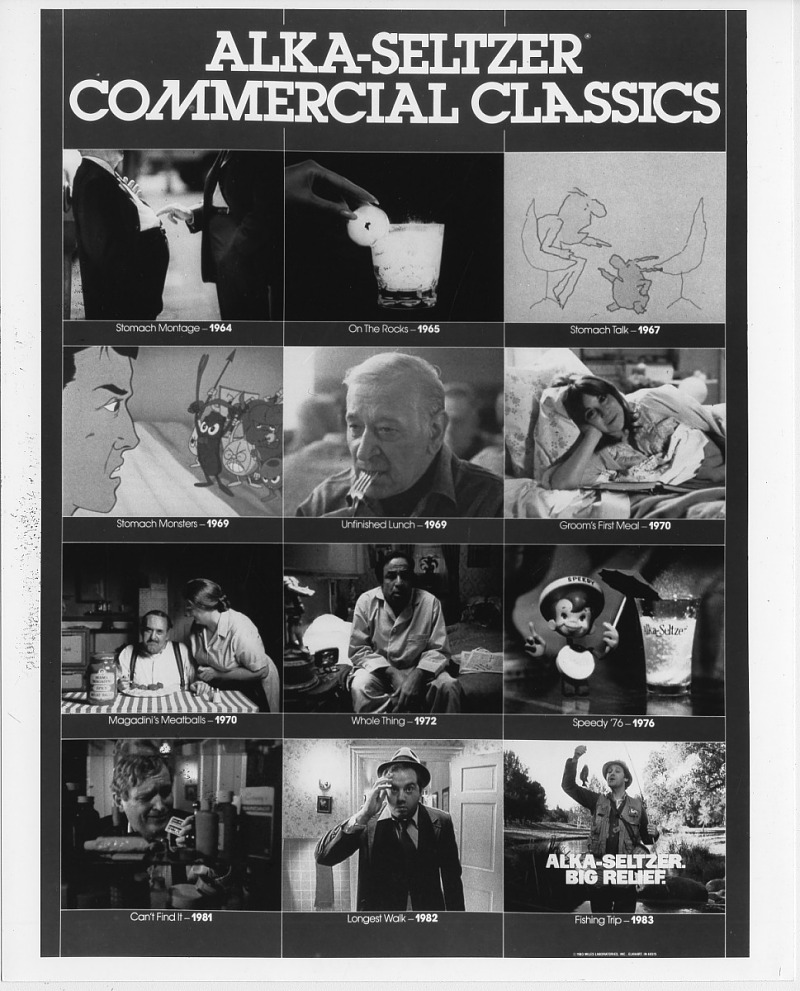

With the advent of television as the complete advertising medium, Gage’s rich exploration of the human comedy found a willing and resonant accomplice. Gage’s distinctive traits of gentle sensibility, lively intelligence and unencumbered feel for the pertinent were given greater expanse and resulted in some of the medium’s most memorable and touching vignettes. It is unlikely that people will forget such masterpieces as Alka-Seltzer’s uproarious “groom’s first meal” and the poignant crackerjack series with the famed comedian Jack Gilford. To call them commercials is to do them an injustice. This was transcendent advertising. To sell a product is the indisputable premise of all advertising. But a Gage commercial does not sell, it convinces.

Awards for Bob Gage and Doyle Dane Bernbach are legion. At one of the Clio Award ceremonies where Bob Gage was honored for his film direction of the Alka-Seltzer and Crackerjack commercials, William Bernbach, speaking of the people in his agency, said, “You have to be nice and you have to be talented. If you’re nice, but untalented, we don’t need you. If you’re talented, but a bastard, we don’t need you. No one exemplifies the nice and the talented better than Bob Gage.” Gage is a leader because he is respected as a doer who is respectful of the best in human communication, and because he is concerned with the professional well-being of his colleagues.

For a short period, Gage assumed the post of Doyle Dane Bernbach’s creative director, only to find that its administrative demands kept him from the excitement that only immediate personal contact with an advertising problem or campaign could give. He has often declined working on prestigious accounts for lesser assignments so that others could be given greater opportunities. Gage remains a pacesetter in a field where imitation is hardly intended as a sincere form of flattery. It is a tribute not alone to his undiminished directorial skill or his adherence to the original purity of the Doyle Dane Bernbach philosophy; it is also a heartening reaffirmation of the good and the true. We live in rapidly shifting times. Some social theorists call it an acceleration of history, others tell us to gird against future shock. Advertising, a far-reaching arm of commerce, can often represent the centrifugal spin of our times in its dizziest, floundering forms. Truth, integrity, quality and dignity are the frequent casualties of the vertiginous thrust for short-range success. Bob Gage, in his flourishing luminous career, has never reached for anything less than full dignity and excellence. Now, more than ever, the field needs staunch standards. Bob Gage, by his work, by his personal mien, and by his devotion to the best of human worth, is the embodiment of those durable standards. He is a model for the modern art director.