Raymond Loewy

1989 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Design, Illustration, Advertising

Raymond Loewy, a pioneering industrial designer, transformed everyday products with his aesthetic vision, influencing brands like Lucky Strike and Studebaker. Born in France in 1893, he became a prominent figure in American design, known for his principle of "Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable," and continued innovating until his death in 1986.

Career

The role of an industrial designer is a difficult one. Through his knowledge of applied art, he must create a manufactured article that will appeal aesthetically to the consumer and result in its purchase. Sales interest, stylistic trends and various other considerations are usually employed to determine how a product should look.

One of the founding fathers of industrial design and certainly the most flamboyant was Raymond Loewy. His influences still reverberate throughout countless design firms and Fortune-5OO companies, not to mention (be it ever so subliminal) the American and foreign consumer. All one has to do is look around. Chances are a fabulous Raymond Loewy-inspired design is right under one’s nose. Witness his contributions to cigarette packaging, automobiles, airplanes, locomotives, corporate identities, refrigerators, duplicating machines, pencil sharpeners and countless other everyday, taken-for-granted items.

Born in France in 1893, Raymond Fernand Loewy, an engineer by trade, served in the French Army Corps during World War I. He immigrated to the United States in 1919. Loewy’s first assignments came as a freelancing fashion illustrator forVogue, Harpers Bazaarand some of New York’s more stylish department stores. His print work for Bonwit-Teller, Neiman-Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue display an urbane, art-deco style popularized during the glitzy decade known as the “Roaring Twenties.” Loewy himself mirrored his designs with his impeccable dress. Whether on a client presentation in New York or sailing on a yacht in Saint Tropez, Raymond Loewy always oozed debonair charm and good taste.

Loewy became a part of a select coterie of designers who unconsciously created and defined what we now refer to as industrial design. Men like Henry Dreyfuss, Norman Bel Geddes, Walter Teague and Harold Van Doren began to plant the visual seeds that shaped the way our nation perceived itself. Their sophisticated, futuristic visions for product designs became synonymous with streamlined modernism and minimalism.

After a short stint as art director for General Electric, Raymond Loewy decided to form his own company. Timing could not have been worse! The year was 1929 and the Great Depression was sending socio-economic shock waves throughout this country the likes of which were never felt before. Armed only with a self-promotional card that read, “Between two products equal in price, function and quality, the better looking will outsell the other,” Loewy went into business. This simplistic axiom was to be his credo for a future filled with immense power, influence and wealth.

Raymond Loewy’s first assignment came shortly thereafter from Sigmund Gestetner, whose duplicating machine still bears his name. Loewy’s challenge was to redesign this cacophonous mass of mimeograph machinery into a more streamlined, productive and safer version. The original design had all of its greasy gears and pulleys out in the open with dangerous, protruding legs that no doubt caused numerous on-the-job secretarial injuries.

With five days to go before his scheduled new design unveiling, Raymond Loewy began modeling his prototype with clay. Out of desperation, he encased the machine’s workings with the grey substance and designed a sleek wooden base with straight legs. Sigmund Gestetner bought it on the spot! As Raymond Loewy reminisced in his 1979 autobiography entitled,Industrial Design,“I often kidded Sigmund about the fact that an exceptionally successful design can make a fortune for the client and put the designer out of businesswaiting 40 years for the next assignment!” That was certainly not the case.

Loewy’s second major break came three years later in 1932 when Sears, Roebuck, the country’s giant retailer, gave him the task of redesigning their Coldspot refrigerator. Realizing its current model was totally out-of-touch with the “modern” kitchen nook, Sears needed Loewy to help holster its slumping sales.

Loewy, via a series of carefully reproduced clay model renderings, created an easy open and close latch, designed food and vegetable fresheners, storage compartments and even a water cooler/dispenser on shelves made of lightweight, rustproof aluminum (now standard on all refrigerators). During the first year on the market, Loewy’s Coldspot sold over 210,000 units, a phenomenal success story given the country was mired in the Depression.

Through Raymond Loewy’s incredible flair for publicity, his name always remained in the limelight and on the minds and lips of top corporate executives. They soon realized that their company’s futures were inextricably linked to Loewy’s genius. Every project he worked on seemed to turn to gold for client, consumer and himself. Loewy’s great success contributed to the expansion of Raymond Loewy International, with offices in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, London, Paris, San Juan and Sao Paolo, giving his operation a much-needed global image necessary to satisfy his “Who’s Who” clientele. With it also came sprawling city apartments and country estates in every jet-set corner of the world. Raymond Loewy lived the fantasy of the rich and famous. Always outrageous and splashy, Loewy loved his work and his clients loved him. Raymond Loewy International became a design supermarket that catered to improving the quality of life through imaginative vision.

Always fascinated with the lure and lore of the automobile, Raymond Loewy could not resist the opportunity to shake up Detroit with his futuristic car designs. First in a long line of radically different, aerodynamic approaches to the box-shaped car was the Hupmobile. The 1932 model was one of the first cars honored by the Classic Car Society of America.

With the success of the Hupmobile came an evolution of Loewy automobile designs that went on to transform BMW, Cadillac, Jaguar, Lancia, Lincoln and Rolls-Royce. His most glowing automotive achievements, however, graced the Studebaker marque with the 1953 Starliner long-nosed coupe and the 1961 Avanti sports car. Both still stand out as glorious examples of Loewy’s adaptive changes to speed with style. They were heralded as “instant classics” and both topped-out at incredible speeds of 170 and 196 certified miles per hour respectively!

Raymond Loewy created what we today call auto ergonomics, ease of operation for the driver in cockpit-like surroundings. As he said of the Avanti, “These cars convey the impression of speed even when at rest.” As testimony to his intuitive automotive designs, an Avanti is on permanent display at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, the only contemporary automobile in their collection.

It would prove futile in the limited space allotted to list all of Raymond Loewy’s astonishing accomplishments in the field of industrial design. Suffice to say, they could fill their own book! In noting the major ones, most people who worked with him seem to suggest the following prime examples.

During March 1940, the president of American Tobacco, George Washington Hill, dropped by Loewy’s office, sat down and tossed a pack of his company’s premier cigarette, Lucky Strike, on his desk. Hill proceeded to bet Loewy $50,000 that he couldn’t improve upon the package design. One month later, Loewy won the bet. The old green pack with red target on one side was gone and immediately replaced with Loewy’s new design. “The pack had to shine, to be moreloo-min-us,” he said in his perfect French accent. The new Lucky pack had a glossy, white background with red targets on both sides. As a result, sales skyrocketed and the unpleasant odor of green ink then in use was also a memory. Were Raymond Loewy to redesign that same pack of cigarettes today, it would have cost Mr. Hill over one-half million 1989 dollars!

Raymond Loewy created and redesigned many corporate identities, Armour, BP, Canada Dry, International Harvester, Nabisco, Sealtest, Shell, TWA, United Airlines and the US Postal Service to name a few. The most challenging, however, came in 1966 when Jersey Standard Oil, better known as ESSO, approached Loewy to change their name and logo. Stemming from a bitter legal battle over brand name identity and infringement brought against ESSO by Standard Oil, Loewy was put to the supreme test: how to change, yet retain a time-tested corporate identity. Legend has it that Loewy huddled his top designers together in a conference room and wrote the word “ESSO” on a blackboard. He then said, “Here is the problem. We have to get rid of the sound of this name.” Loewy picked up the chalk and put two Xs through the two Ss and the name EXXON was born! Loewy believed ESSO would subconsciously be recalled by consumers with EXXON and the idea worked.

In his book, Loewy relates an amusing anecdote that sums up the EXXON project: “At a dinner party in Palm Springs, a lovely young lady asked me ‘Why did you put two Xs on EXXON?’ I asked her ‘Why ask me?’ She said ‘Because I couldn’t help seeing it.’ I replied ‘Well, that’s the answer.

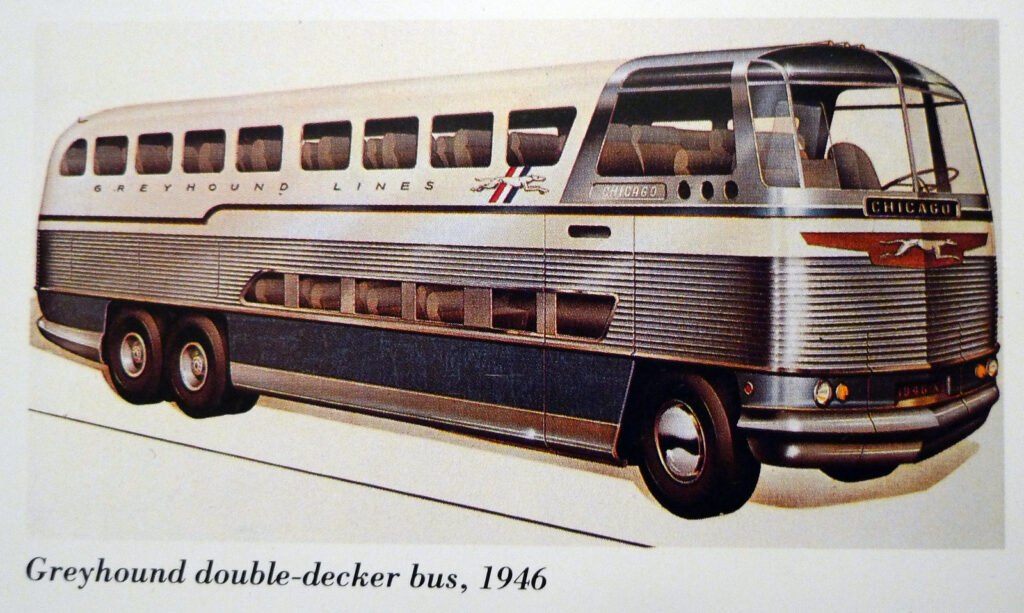

With soft pencils, scrap paper and scissors always at hand, Raymond Loewy continually needed to express himself visually and encouraged his employees to do likewise. He created the principle of MAYA, “Most Advanced, Yet Acceptable,” and put it to use when he designed everything from locomotives, steamships, department stores and space suits to electric shavers, Greyhound buses, the Concorde interior, Skylab and Air Force One. Raymond Loewy forever changed the visual landscape of America. He was the consummate art director because to Loewy everything was art. He orchestrated an entire legion of loyal followers, many of which have gone on to head their own ateliers based on the Gospel-according-to-Loewy.

He has received innumerable awards and recognition for his lifetime of achievements. Loewy was proudest of the 1949Timemagazine cover story proclaiming him the “Streamliner of the Sales Curve” and historian Daniel J. Boorstin’s selection of Loewy inLifemagazine’s bicentennial issue as “One of the 100 great events that shaped America.” Not content to rest on his domestic laurels, at the age of 82, Raymond Loewy ironically became a design consultant to the USSR.

Times changed and some of Loewy’s magic just couldn’t keep up with society’s frenetic pace and popular appeals. He was no longer the Pied Piper of industrial design and because he lived so long, far surpassing any of his contemporaries, Loewy became revered for his former innovations, not his latter ones. In the late 1970s, Raymond Loewy International was sold to a banker, marking the beginning of the end for his almost mythical design empire.

Raymond Loewy died in 1986 at the age of 92. His place in American industrial design is forever secure. He was a legend in his own time and was driven by an inner force that wouldn’t cease until the quality of life for people was completely fulfilled. That’s why Raymond Loewy continued to work right up until his death.

Two former design directors of RLI, John Lister and David Butler, said in a letter to the New YorkTimesshortly after Loewy’s obituary appeared, “Raymond Loewy dramatically altered the look of American life by bringing his streamlined style to nearly every aspect of our lives. He was alone among the giants of design in this century in his understanding of the relevance of design to everyday life.”