Norman Rockwell

1994 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Illustration, Advertising, Design, Education

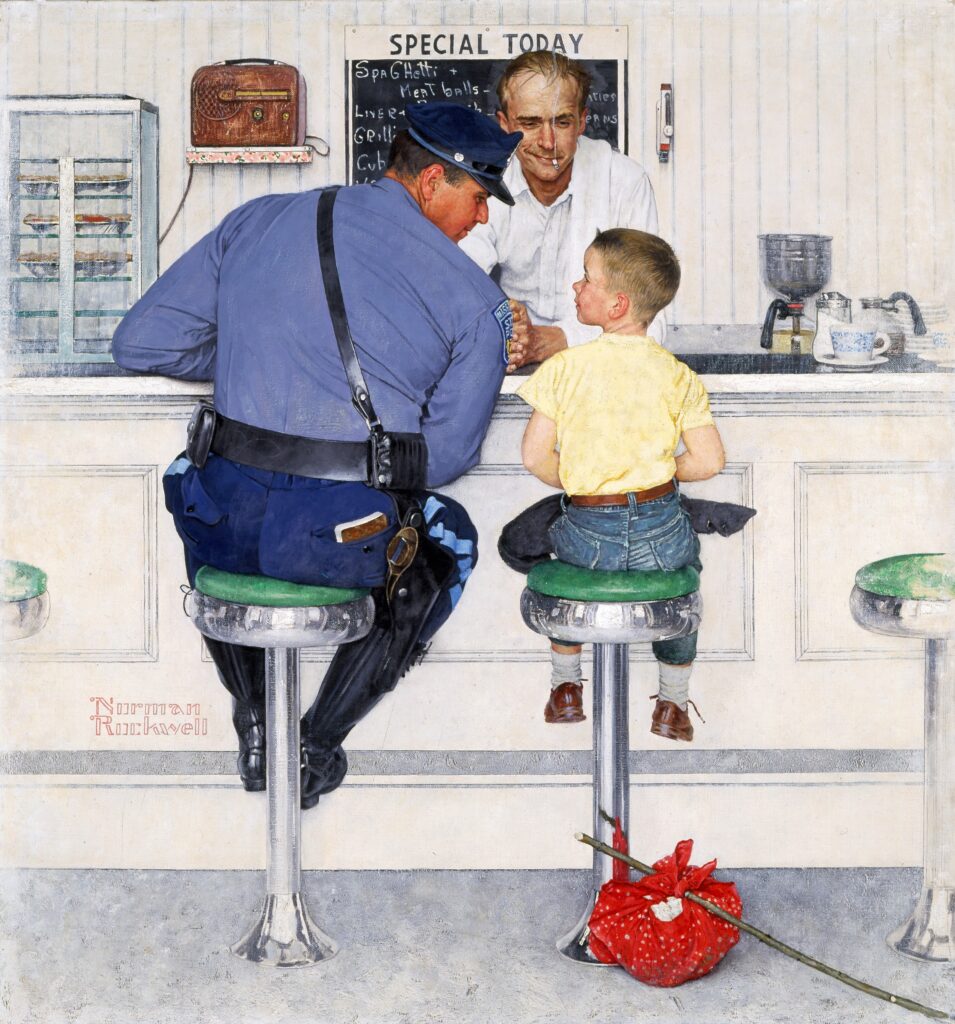

Norman Rockwell, born in 1894, was a renowned American illustrator known for capturing the essence of American life through his art. Despite an early oath to avoid commercial work, he became famous for his illustrations in magazines, particularly the Saturday Evening Post, and later addressed serious social issues.

Career

Shortly after the turn of the century, three young art students swore an oath: they signed their names in blood, swearing never to prostitute their art, never to do advertising jobs, and never to make more than fifty dollars a week. One of these blood brothers dismally failed to keep his allegiance. His name was Norman Rockwell.

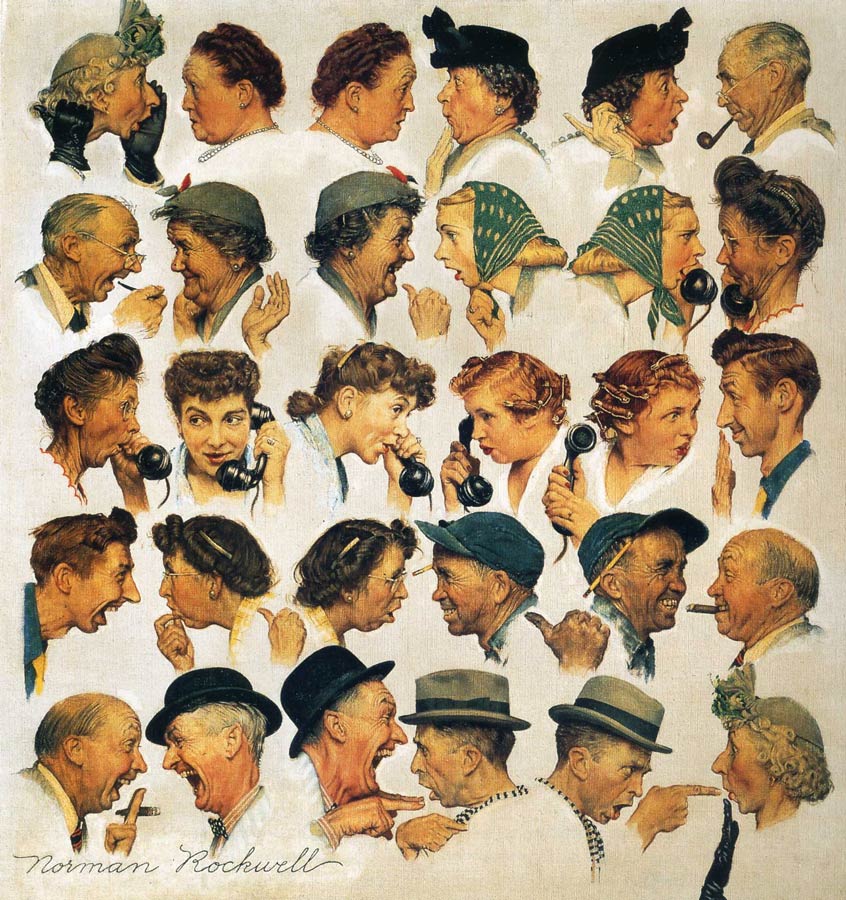

To the millions of Americans whose lives were touched by his work, he is the best known and best loved illustrator of the twentieth century. For nearly seven decades, Norman Rockwell chronicled on canvas the heart and soul of America. In many of his best-known works he visually idealized the clean, simple country life of his childhood. In others he introduced middle America to the products of progressive urban life: the telephone, radio, electrical lighting, television, airplane travel, and the space program. Later in life, he devoted himself to more serious subjects: civil rights, the war on poverty, and the Peace Corps.

Norman Rockwell was born in New York City on February 3, 1894. As a child, he was drawn to country life: delighting in the summers his family spent on an upstate New York farm and their eventual move to Mamaroneck, New York.

He discovered that he had a natural talent for drawing. Since he wasn’t built for athletics, he decided to work toward the goal of becoming an illustrator. In 1909 he left high school and enrolled full time in the National Academy of Design. Soon after, he switched to the Art Students League, which was the most progressive school of that time. There he studied under George Bridgeman who tutored him in the rigorous technical skills he relied on throughout his career.

Unlike most illustrators, Rockwell didn’t have to face the usual hardships. His work always sold. At fifteen, he painted and sold four Christmas cards. He began a successful freelance career illustrating. He did ads for Heinz Baked Beans, two books for the Boy Scouts of America, and numerous magazine illustrations. Three years later, he was hired as an illustrator forBoys Life. Within a few months, he was promoted to art director. He only held the position for a few years, but the relationship he established with the Boy Scouts lasted for the rest of his life.

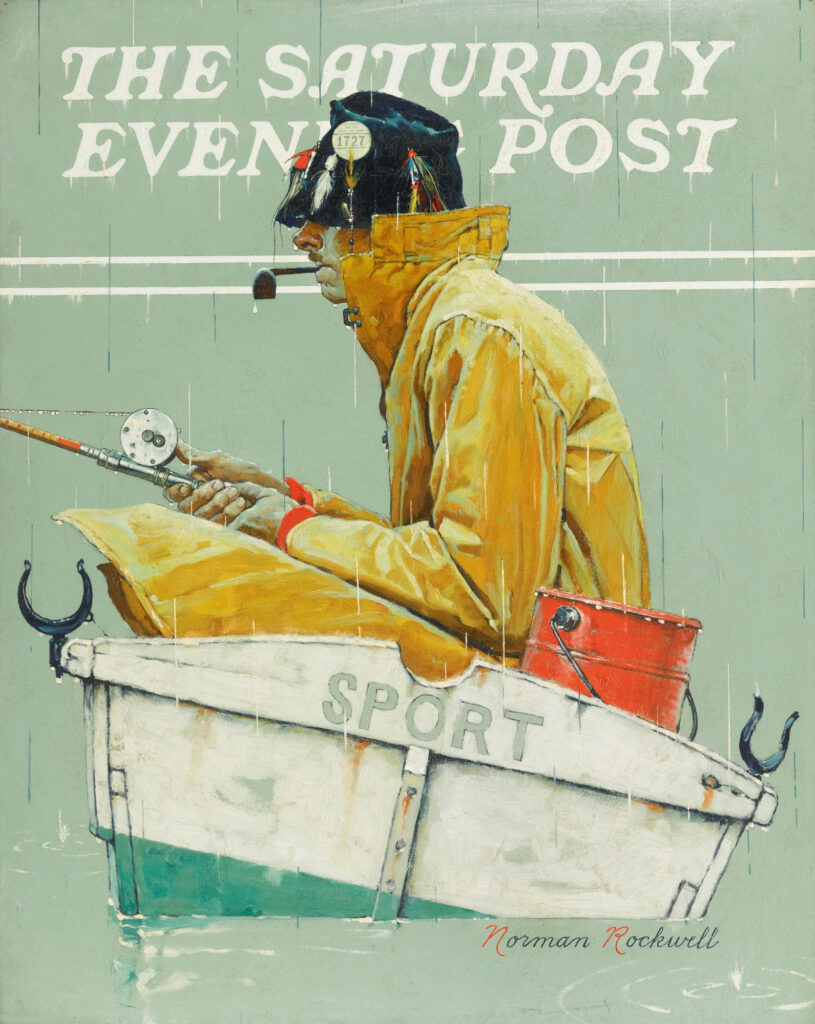

Rockwell established his own studio in 1915 with cartoonist Clyde Forsythe. From this New Rochelle studio, he worked for popular magazines of the day:Country Gentleman,Literary DigestandSt. Nicholas. The next year, he painted his first of 321 covers for theSaturday Evening Post, “Boy with Baby Carriage.” Rockwell used one model for all three boys featured in the illustration. It best displayed his talent to create a variety of characters from the same subject.

He joined the navy during World War I and served as the art editor forAfloat and Ashore, the house publication for the Charleston, South Carolina Naval Reserve Base. His other duty in the service was being the naval officers’ portrait painter. He was still permitted to do civilian work: his covers still appeared on thePost. A cover commission forLifemagazine, “Over There” was later used on the cover of the sheet music for the song of the same name.

During a 1923 trip to Paris, Rockwell became enamored with the modernist movement. He proposed a number of works with modem influences to theSaturday Evening Post; they were horrified. Despite their reaction, traces of Picasso, Van Gogh, Pollock, Rembrandt, Sargent, and Drer occasionally appeared in his work.

In the 1920s, Rockwell’s client list grew from leading publications to product advertisingillustrating everything from automobiles to Jell-O. In 1925, the first of fifty annual Boy Scout calendars featuring Rockwell’s work was published.

Though he had been quite successful and productive in the twenties, his popularity hit its all-time peak in the forties. After he moved his second wife and three children to Arlington, Vermont, he set to work on his contributions to the war effort. As America came together to support our troops in World War II, he turned his talent toward producing, among other works, a series based on a Franklin Delano Roosevelt speech, “The Four Freedoms.” The paintings became the main attraction of a nationwide fund drive that helped sell over $132 million in war bonds. At that time, Rockwell’sPostcovers depicted life on the home front, or the adventures of Willis Gillis, his characterization of G.I. “everyman.”

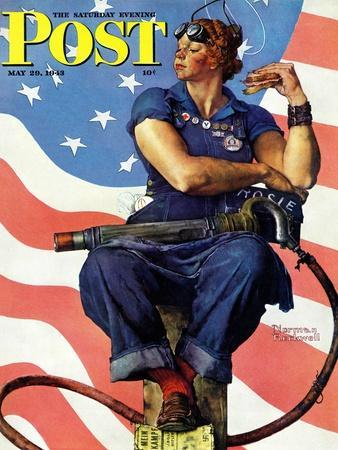

Another memorable character Rockwell created was “Rosie the Riveter,” the symbol of women involved in wartime production. Familiar images like “Rosie” and “The Recruit” were based, according to Rockwell, on works by Michelangelo. Rockwell sought to transpose the master’s figures onto his models and transform them into modem middle-American icons. (Perhaps as an acknowledgment of the source of his inspiration, Rockwell placed a pale Renaissance halo over the head of his lady riveter.)

In the fifties Rockwell moved to Stockbridge, Massachusetts. There he was commissioned to do the first of two decades’ worth of presidential candidates’ portraits. He also produced a series of Hallmark Christmas cards, began a series ofFour Seasonscalendars for Brown & Bigelow, and a series of ads for Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company. At the same time he continued his long-running relationship with theSaturday Evening Post. ThePosthad gone through many redesigns in forty-five years, and in 1961, Rockwell depicted all of its changes as they lay strewn aroundHerb Lubalin‘s drawing table.

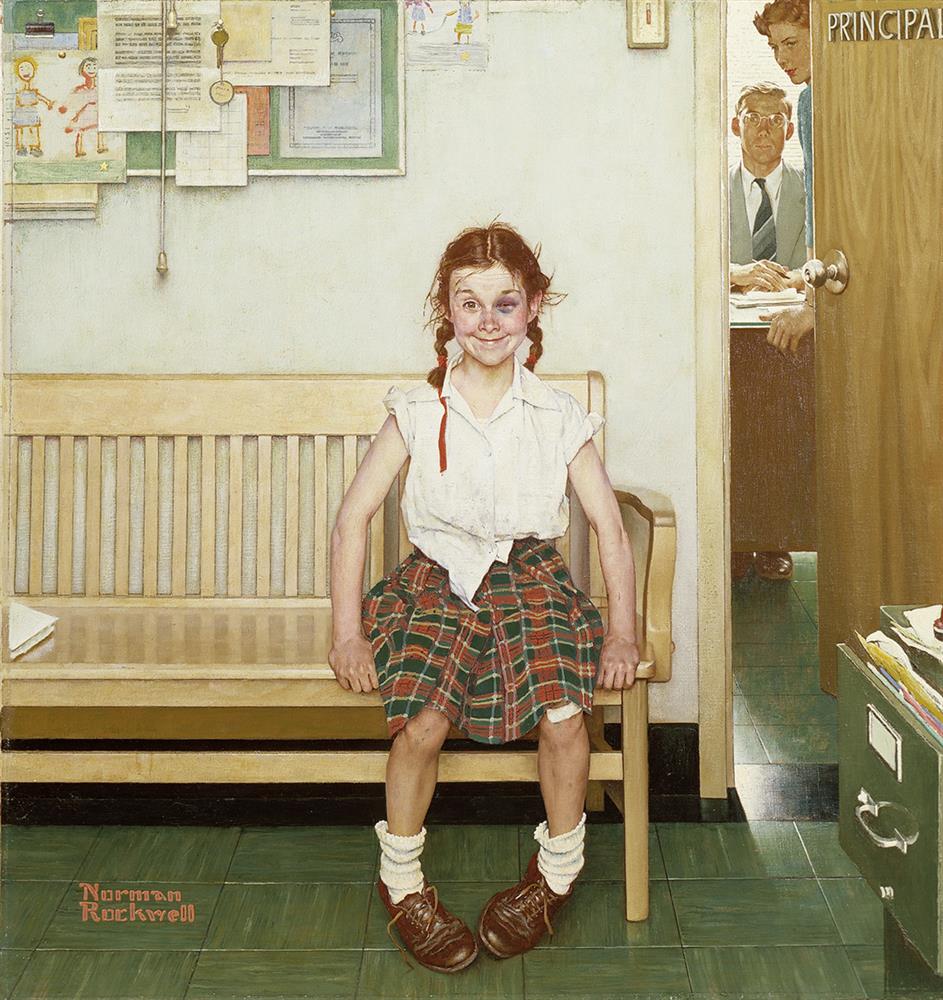

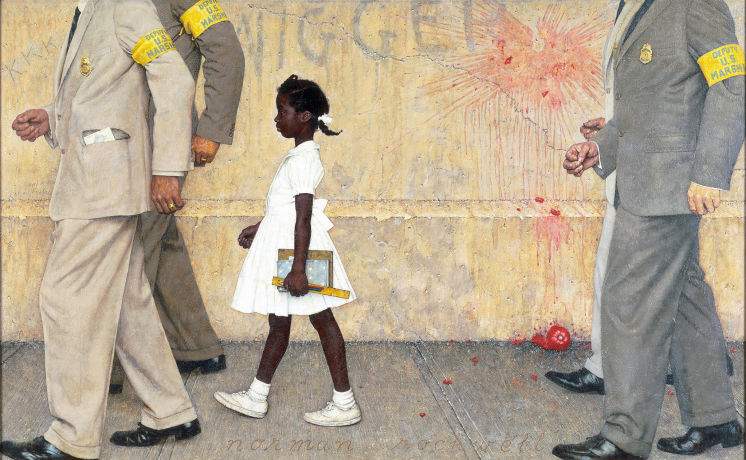

America had lost its veil of innocence. In the notes for a speech, Rockwell reflected: There was a change in the thought climate in America brought on by scientific advance, the atom bomb, two world wars, and Mr. Freud and psychology Now I am wildly excited about painting contemporary subjects … pictures about civil rights, astronauts, Peace Corps, poverty programmes. It is wonderful.”

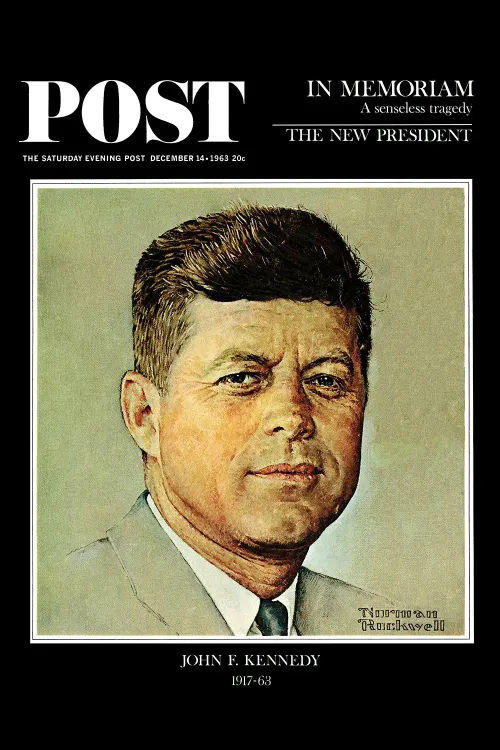

As a result of this new consciousness, Rockwell severed his long-standing relationship with the ultra-conservativeSaturday Evening Post. In one instance, the magazine rejected his cover depicting Yugoslavian premier Marshal Tito as the only hope to unite the Serbs, Bosnians and Croats in Yugoslavia because it portrayed a communist leader in a favorable light. Rockwell’s last Post cover was published in December 14, 1963. It was a reprint of his famous 1960 John F. Kennedy cover portrait with an added caption, “in memoriam.

Rockwell then accepted a number ofLookmagazine commissions. His first cover for them The Problem We All Live With” focused on the Civil Rights movement and specifically school desegregation. Another, “Southern Justice,” condemned violence against blacks and civil rights workers. A stark image of three men being murdered by a group of shadows was executed in tones of brown and grey except for a flow of red blood on one man’s shoulder. This was a radical departure for a man who for nearly five decades had been depicting wholesome folk in classic scenarios. Interestingly,Lookopted not to publish the finished painting of “Southern Justice.” Instead, they ran his more impressionistic color study.

Rockwell never referred to himself as an artistalways as an illustrator or commercial artist. Artists, he felt, were people who painted what they wanted, not what they were paid to paint. Would he have believed it if someone told him that his works would soon fetch $150,000 to $300,000 at auction?

Detractors who take the time to study his work are surprised to find that it doesn’t lack in inspirational depth, despite its accessibility, yet, in most art history textbooks, his work is not included along with another twentieth-century illustrator, Andrew Wyeth. He is not hailed for his contribution to the visual history of America as are Remington and Sargent. There are signs, however, that he will eventually be counted amongst the great twentieth-century American artists. There is a diverse group of Rockwell collectorsthe Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Smithsonian, The National Portrait Gallery, the Corcoran Gallery and Steven Spielberg.

The Norman Rockwell Museum opened in 1993 in Stockbridge, Massachusettsone of the few American museums to grow out of popular demand for a single artist’s work. The museum became a necessity after Rockwell agreed to lend some of his works to the Stockbridge Historical Society in 1969 for a permanent exhibition. Word spread that his works were on display and attendance swelled from 5,000 people up to the current 160,000 annually.

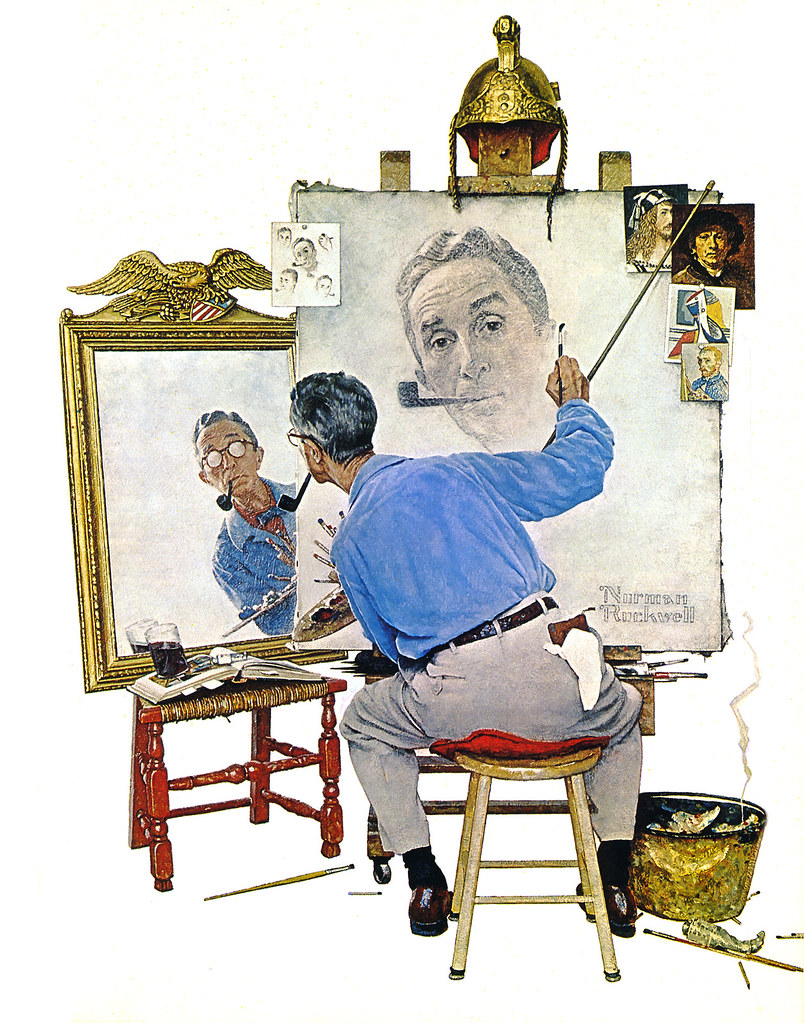

Compared with his achievements, to mention the awards and honors he received would seem anti-climatic, except for two. In 1977, President Gerald Ford presented Norman Rockwell with the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his “vivid and affectionate portraits of our country.” And on July 1, 1994, Norman Rockwell took his place next to Elvis and other American icons when the United States Postal Service issued a commemorative series of five Rockwell works including “Triple Self Portrait” and “The Four Freedoms.”

The simple eloquence of his familiar style belies his painstaking creative process. Each painting began by carefully setting up the scene and photographing it or sketching it from life. After a series of black-and-white pencil sketches, he would do color studies. The final oil painting would invariably include the excruciatingly minute details that make his work nearly impossible to forge.

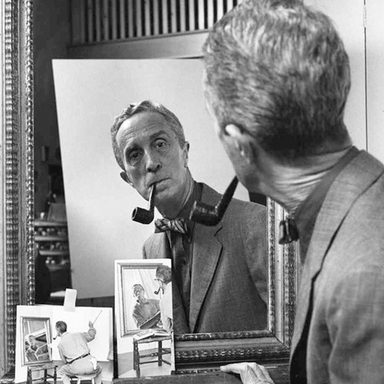

Robert Campbell of the Boston Globe commented: “The mistake most of us make is to think of Rockwell as a realist. He wasn’t, really. For starters, his people usually don’t even cast shadows. They don’t seem to have any weight or mass. They touch the ground but don’t exert pressure on it. Often the ground itself is vague and white, like a cloud. Rockwell’s people aren’t so much flesh and blood as they are likeable everyday gods and goddesses, inhabiting American mythological heaven.” In “Triple Self Portrait,” Rockwell composed three images of himself placed in some illustrious companyVan Gogh, Picasso, Rembrandt and Drerwhich he included as reference studies tacked on one comer of his canvas. He admitted to being influenced by both classic and modern fine arts masters.

And like other masters, Rockwell had a unique talent for uncovering the everyday, human side of even his most famous subjects. He preferred common faces. He compared the excitement he felt painting the face of a successful person to a slab of warm butter. He readily admitted that the America he depicted was the country he hoped it could be, and considered his pre-1960s work to be more escapist than realist. There are few artists who better exemplify the dichotomy between high and popular art in the twentieth century than the man who gave Americans an endearing and enduring vision of themselves.

-Anistatia R. Miller

Photo credit:Clemens Kalischer