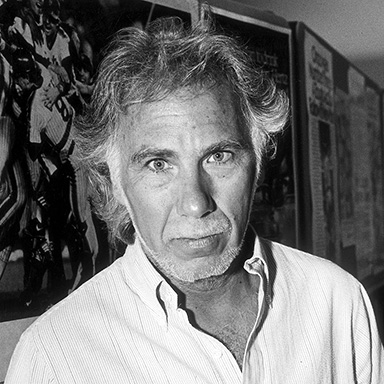

Mike Tesch

2004 Creative Hall of Fame Inductee

Advertising, Design, Illustration

Mike Tesch is a bold art director known for his use of primary colors and a primitive style. He excelled in both print and television advertising, creating impactful campaigns for clients like Pan Am and Federal Express. His innovative approach and mastery of both mediums set him apart in the industry.

Career

Mike Tesch squeezes only primary colors out of paint tubes. He never

mixes complimentary pigments. His palette includes no tints or shades,

no subtle hues or grey values. Armed with Magic Markers to render a

layout or storyboard in his primitive style, his color spectrum is RGB with

few additions. Nothing to dilute impact.

For purposes of clarity, Grandma Moses is a delicate primitive; Mike Tesch

is a fiery primordial.

His flat bold technique, without the need for florid detail, was all that was

necessary to capture the essence of his ideas. Nuances and refinements of

his work were reserved for in-person explanations. An efficient use of time.

His personal signature would dwarf John Hancock’s. It requires a spread.

These are just a few small observations among many I’ve come to make about a man with whom I have

worked longer than any other.

Tesch emerged from a graphic design discipline. Early in his career he was employed by two giants

in the field: Chermayeff & Geismar, but soon became eager to move into advertising. He took

a job with a boutique agency, Fladell, Winston & Pennette, and a short time later, in 1966,

joined our four-year old agency as an art director, where he felt an affinity with our dogged

determination to change advertising.

I watched him grow into a confident print art director, working first on Hertz under the careful

tutelage of one of our group heads-also an inductee into the Creative Hall of Fame-the brilliant

Ralph Ammirati. Soon afterward, he plunged headlong into a nervous transition to television with

his first commercial for Northeast airlines.

In time, Mike became omnipotent. He conquered the art of this demanding medium of television as

convincingly as the medium of print. No small accomplishment. Because, at the highest standards

of both, few art directors gained equal mastery. Art directors who moved easily between print

and television with superb skills, range of emotion and understanding, and depth of message

are few in the history of advertising. Men and women who became giants in the business more

often than not dominated only one media.

Except for one pioneering art director who was the first to freely traverse print and television

with equally remarkable wit and style, intelligence and humanity, and set a standard so high that

very few among the legendary art directors during his time-and those that followed-could

match. That man whom Phyllis Robinson, his long-time creative partner, so eloquently praised at

his induction into the Creative Hall of Fame 20 years ago, was Bob Gage.

I would include Mike Tesch among that rare group of art directors.

A campaign he created for Pan Am with the gifted writer, Tom Messner, helped the airline achieve

$119 million in profits by 1978. In marked contrast, advertising created by Pan Am’s previous

agency, helped record much red ink. Of lesser importance to the business community, but of

greater value to advertising, the campaign established a paradigm for airline advertising anchored

by a theme line that read: “Every American has two heritages. Pan Am would like to help you

discover the other one.” The work ran the year before Alex Haley’s breakthrough mini-series,

Roots, appeared on network television. Not surprising, Pan Am became an appropriate sponsor.

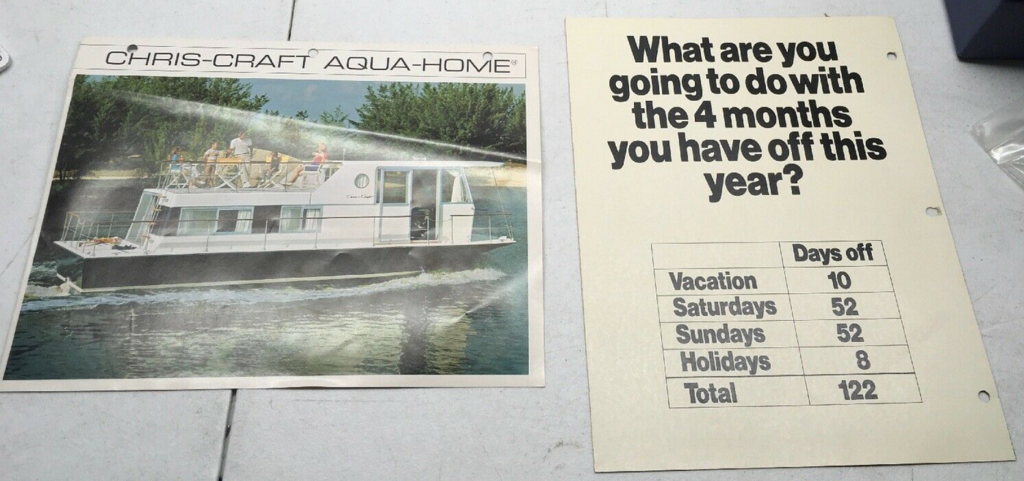

For a client near Lake Minnietonka, Minnesota, Mike brought to life the farcical excuse of young

boy with a broken toy from a previous Tonka commercial who said: “An elephant stepped on it.”

And so, in a classic demonstration, an elephant did step on a Tonka truck without a ding to the

toy. And another gold medal commercial. For dry subjects like insurance, he brought humor

and irony in persuasive print ads and television commercials for Travelers.

Work he created for Federal Express with his incomparable writer, Patrick Kelly, is legendary.

Together their advertising helped grow the company from a nightly average package delivery

of 30,000 in 1977 to 700,000 in 1986. Among the multiple gold medals won for Federal Express

for both print and television, “Fast talking man” may be the most honored television commercial of

the twentieth century.

My most persistent memory of Mike Tesch is that of a man alone, hunched over a drawing table in

a darkened room, ceiling lights turned off, blinds drawn tightly with no chance for sunlight to peek

through. A small rim of light from a drawing lamp pulled close to his work prevented light from

spilling elsewhere into the office.

All the illumination that was needed came from his fertile mind, which, over the years, helped

make advertising shine.

Amil Gargano