M.F. Agha

1972 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Design, Typography, Illustration, Photography, Education, Advertising

Mehemed Fehmy Agha, a Russian-Turkish artist, revolutionized magazine design as art director of Vogue in 1929. His innovative approach integrated art direction into editorial processes, enhancing visual storytelling. Agha's influence transformed American publications, introducing modern photography and typography, while fostering a culture of creativity and excellence in graphic arts.

Career

In the halcyon days of 1928, before the great economic crash that shook the country and the world, magazine publishing was a considerably less beleaguered business than it is today. An earlier century’s tradition of personal enterprise was still alive and many publishing companies were imprinted with the name and style of the founder. Conglomerates and diversification were decades away and times were such that even a major publisher-owner could play an active role in the day-to-day operation of his publications.

Among the leading magazines of the period, Cond Nast’sVogueandVanity Fairand, to a lesser degree,House and Garden, enjoyed a special prestige and exerted a pioneering cultural influence. The art director then, at least within the Nast organization, was known as art editor. As events in that year would have it,Heyworth Campbellhad resigned his post as art editor, which in the words of Cond Nast, “he had held so long and filled so well that I hardly knew where to look for a substitute.”

What started as a search for a “substitute” was, by good fortune, to lead to a fundamental change in modern publication design and the consequent transformation of the role, importance and contribution of the art director in editorial planning and organization. Cond Nast’s odyssey took him to London, Paris and Berlin, whereVoguewas publishing its foreign editions. Finally, in Berlin, he interviewed a young Russian-Turkish artist with the intriguing name of Mehemed Fehmy Agha, who had been sent from Paris, where he had been studio chief at theVogueheadquarters, to work as the designer of the GermanVogue. Nast was impressed by the “order, taste and invention” of what he had seen in Agha’s work. Nast’s humorously self-deprecating report of the interview is enjoyably descriptive of a time and bygone style; more importantly, it is a candid first snapshot of the thirty-year-old Agha’s captivating intelligence and persuasive personality. In speaking of similar interviews he had had over the years with an array of aspirants, Nast recalled, “I had always in those discussions analyzed scores of back issues ofVogue, rival publications and foreign periodicals, in order to expound my theories, convictions and prejudices in the matter of makeup. And I had invariably in such sancesand perhaps with too great an assuranceassumed the role of teacher.” A day later, Nast announced to his companions-in-questEdna Woolman Chase,Vogue’sdoyenne editor, and Frank Crowninshield, the much quoted editor ofVanity Fairthat at last the ideal art director forVoguehad been found. Mrs. Chase, a woman not easily convinced, asked how Nast was so certain. Nast’s reply was that in Agha he had found a man with whom he could not assume the role of teacher, “since he had at our extended interview, assumed that role himselfafter relegating me politely to the dunce’s corner where apparently, he thought, I really belonged.” Nast took the role reversal in the appropriate good spirit, at the same time realizing his unusual good fortune in discovering Agha.

Early in 1929, M. F. Agha came to the United States to assume the art direction atVogue. It did not take long before it was clearly evident that M. F. Agha was no ordinary art director. Whether it was out of deference to his extraordinary educational background, or because of his impressive personal style or charisma, he was known and addressed almost from his first day at the Conde Nast command post as Dr. Agha.

Agha was born in Russia in 1896. His Turkish parents belonged to a tribe, Frank Crowninshield wrote in 1939, “of which there are now less than ten thousand members in the entire world, only one of them, I believe, an art director.” His education in Czarist Russia included a graduate degree in economics from the Emperor Peter the Great Polytechnic Institute and earlier training in the arts at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kiev, as well as at other distinguished Russian institutes. After leaving Russia, he received a special degree in 1923 from the National School of Modern Oriental Languages in Paris. Beyond a far reaching cosmopolitanism (he was fluent in Russian, Turkish, German, French, Greek and English) and a strong technical and scientific background, Agha was an accomplished artist, photographer, and typographer. In sum, he was a man whose erudition and aesthetic sensibilities especially fitted him for the role of director, teacher and tastemaker.

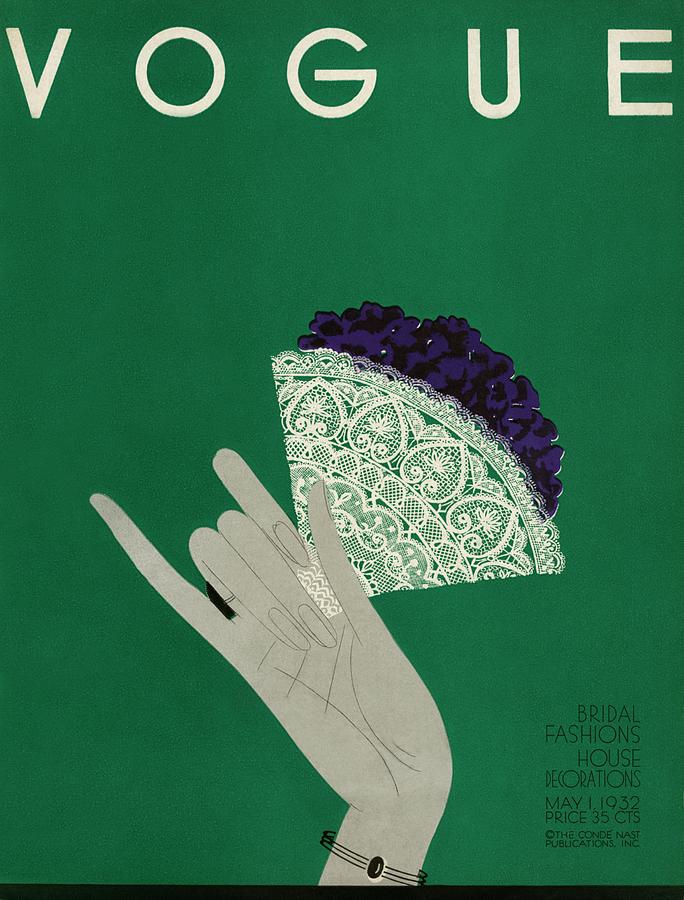

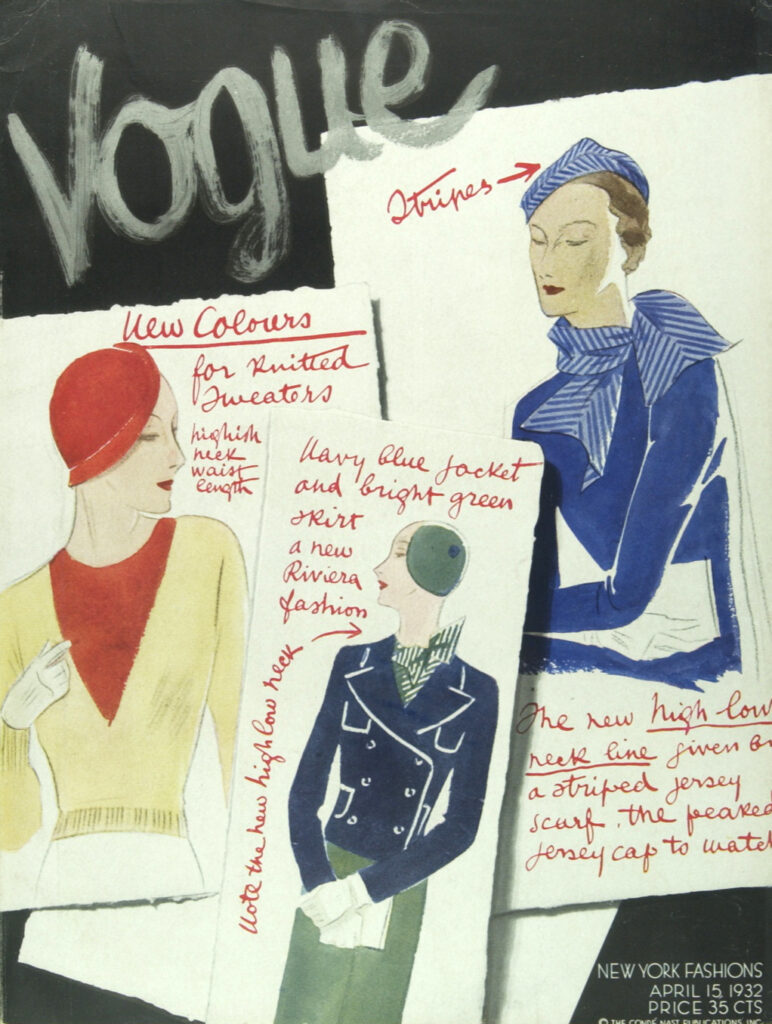

The times and the problem at hand demanded a commanding figure of no less a happy confluence of qualities. TheVogueandVanity Fairof the late twenties, while sophisticated leaders in their respective editorial domains, lagged rather cheerlessly in matters of visual concept and design. Whereas its writing and conceptions were sparkling, witty, and adventurous, the visual vehicle for this bright panoply of content was tedious and unchallenging. If Agha changed the course of matters, it was the matter of course that he changed first. Agha introduced a radically new principle in the conception of modern American publicationsthat of the participatory role of the art director at every level. The visual articulation of a magazine was not to be an act after the editorial fact; it was, as Agha saw it, an integral function of the editorial process. As Cond Nast himself was to revise his preconceptions in that Berlin meeting, so Agha by intellect and achievement was able to shatter the ossified conceptions of art direction. In transforming the magazines whose artistic destinies had been placed in his hands, Dr. Agha broadened and raised the level of art direction. Design was no longer regarded as a decorative adjunct, or as gifted mechanical skill, but as an organic function of the modern publication.

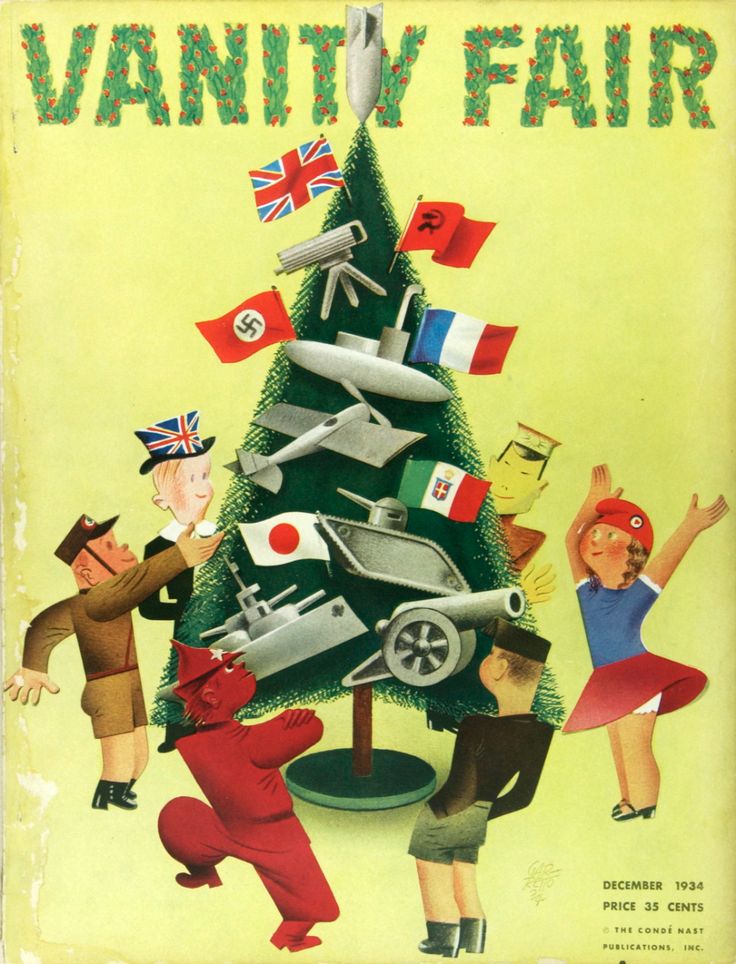

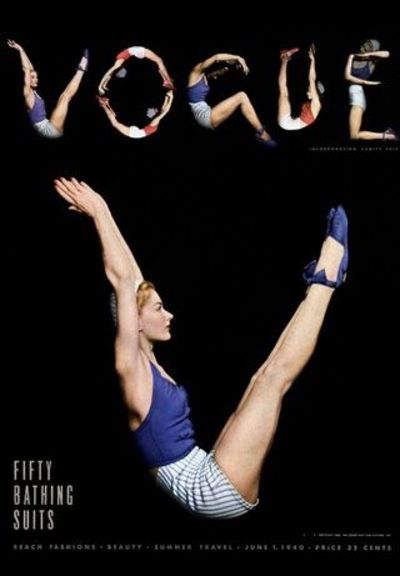

Agha immediately broke through the restrictive antiquarian ideas of page layout, photography and illustration. A highly imaginative photographer himself, he introduced many of the illustrious forerunners of modern photographyEdward Steichen, Cecil Beaton, Hoyningen-Huene, Horst, Carl Van Vechten, and Charles Sheelerwhose work influenced the generations that followed. In addition, he created an entirely new form of fashion art. Artists whose work seemed remotely distant from the gossamer world of fashion were given the encouragement of a cultivated far-seeing taste. Willaumez, Pages and the immortal Carl Ericson (known professionally as Eric) were only a few of the brilliant draughtsmen whose creations added genuine lustre to a glimmering world. But it was not only to that brittle scene that Agha brought innovation.Vanity Fair, with its wide compass of interests, invaded the arts, politics, and the social scene. Almost any subject was fair game for the best writers of the time. Gertrude Stein might well share an issue with John Gunther, Thomas Wolfe, Lord Dunsany or Dorothy Parker. Not only did Agha provide that galaxy of talent with a worthy visual counterpart, but a man of no mean wit himself, he also fathered the notion of the pictorial feature, wherein pictures proved they more than outweighed the proverbial thousand words. In the realm of sociopolitical comment, Agha was the impresario who guided Miguel Covarrubias, the Mexican artist and archaeologist, into the world of trenchant satiric commentary. His illustrations for the legendary “impossible interviews” and numerous political covers created an editorial point of view that still nourishes modern artists and publications.

In the Agha reformation, typographic style was purified. The sans serif type styles of Europe were introduced to American designers and readers. Agha’s strong scientific background enabled him to work in a highly technical way with photographers and engravers. He set up and conducted complicated engineering experiments in an effort to give the artist and photographer a printed page in color that was worthy of the art that graced it. In that scintillating era, there was also the teacher-leader side of Aghathe director of people as well as of magazines. Among those who worked with him in those Cond Nast days, he is remembered as a man of penetrating insight, unequaled wit, and at times, like the brilliant chess player he is, of dazzling intellectual wizardry. His role was to keep the mold of self-satisfaction from forming and to make co-workers ever suspect of things shoddy. If his criticism stunned, it was to stir the artists and designers about him to search deeper within themselves for the answers they could not foresee to graphic problems. Among those who worked with Agha wereCipe Pineles,William Goldenand Tobias Moss. Most have gone onto a fame of their own.

After ten years with the Cond Nast organization, Agha was honored by the journalP.M., which was then published by the typographic house, Composing Room. The entire issue was devoted to Agha, carrying articles and graphic tributes from those who were his colleagues. The late William Golden wrote a tribute to Agha, which, in Golden’s own crisp way, was an unusual critical appreciation of the inner man. Golden saw Agha as a man who was in the grip of ennui engendered by his own brilliance. Golden refers to Agha’s style of finally choosing the design of an editorial page and his method of keeping his subordinates off balance: “This method may, to some shortsighted people, seem cruel and unjustified, but I submit that an artist who is suspicious of his own work is more likely to look for new forms of expression than one that is self-satisfied. And for sheer productivity this method is unequalled.”

Agha continued at Cond Nast until 1943. During his fourteen years there, he had achieved unmatched eminence and was awarded numerous honors. It was only six years after his arrival in New York that he was selected to be the President of ADC.

After leaving the magazine world, Dr. Agha was an active graphic and directorial consultant for numerous corporations, department stores and large publishing companies, contributing his extraordinary expertise to the solutions of varied advertising and promotional problems. Yet by reason of almost cynical disbelief in the permanence of his achievements, he eschewed any collected exhibition of work, neither did he welcome a special tribute to his professional contribution. As William Golden wrote thirty-three years ago, “Mehemed Fehmy Agha is an unhappy man. He has learned nearly all there is to know about the graphic arts, only to discover that he never liked them in the first place.”

Deeply affected by the death of his wife in 1950, Dr. Agha steadily reduced his consultant activities and turned to the myriad pursuits of an intellectually restless mind.

Every discussion or recollection of Dr. Agha in his most active time is tinged with the most evocative memories: his wit, urbanity, even his elegant snuffbox and railroad man’s handkerchief. Had it not been written two hundred years earlier, Buffon’s observation “style is the man himself” might well have been suggested by Mehemed Fehmy Agha.

Unique as he was a personality, Agha was as uncommon an aesthetic presence that transformed his and our time. He brought an aesthetic acumen that cut through the thickets of outworn ideas to create a new legibility, a new logic and a new elegance to printed communication. Above all, he brought an endless replenishment to the springs of inspiration.

Please note: Content of biography is presented here as it was published in 1972. Photo by: Horst P. Horst