Lester Beall

1972 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Design, Education, Advertising, Illustration, Typography

Lester Beall, a pioneering graphic designer, thrived as an independent artist, influenced by Chicago's maverick spirit. Educated in art history, he gained recognition for innovative posters in the 1930s. Beall's work combined artistic freedom with Bauhaus principles, leaving a lasting impact on American graphic design until his death in 1969.

Career

In 1960, after nearly twenty-five years of distinguished accomplishment as an independent designer, Lester Beall, in a look backward, reflected, “It is very difficult for me to imagine ever having, even on rare occasions, considered the possibility of working within an established organization.” It was said without bravado, and Beall hastened to add that the independent practitioner required “a certain kind of personality.” Beall’s views, like his work, were never offhand or meretricious, and his observations were always thoughtful and articulate. Apart from these singular personal attributes, Beall picked up some additional spirit of independence from his formative years in Chicago. That Midwestern city has a noble tradition of mavericks, having produced a constellation of people who earned their reputation by struggling against and triumphing over the conformist tide. Chicago, it is to be remembered, was where the scattered pieces of the dismembered Bauhaus were put back together, and its design beliefs revived.

Beall was born in Kansas City, but he received his formal education in Chicago. Curiously enough, it was not as a designer. Initially, he attended one of the city’s technical schools, and from there he went on to the University of Chicago, earning a degree in art history. Beall, however, was able to make an immediate and successful leap into what was then the “terra incognita” of graphic design. Doubtless, Beall was gifted with considerable, if yet unexplored, talent, but the supporting ingredients were his keen intelligence and a capacity for intellectual inquiry. Beall remained in Chicago until 1935, always working independently, and it was not long before he began to gain professional recognition. Prior to his departure from Chicago, he created exhibits and murals for two large companies participating in the Chicago World Fair of 1934. That period also marked the first appearances of his graphic design in an Art Directors Annual. Two aspects of that early work created an interesting interaction that Beall retained throughout his professional life. One side was Beall the artist, infatuated with the freedom of the artist’s language. The other side was the designer captivated by the Bauhaus ideology and absorbed by the discipline of visual engineering.

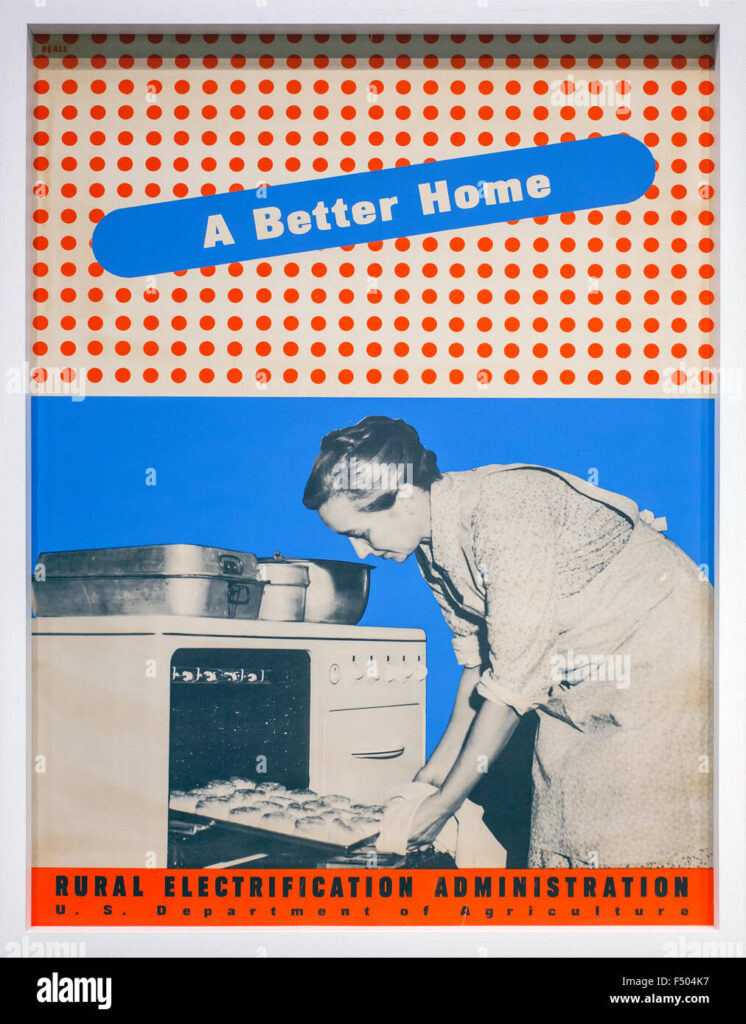

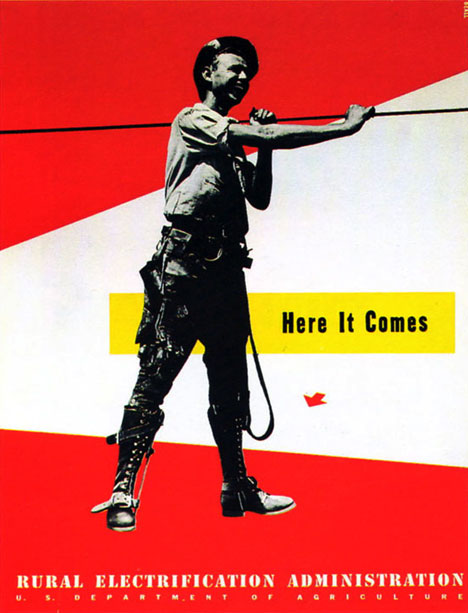

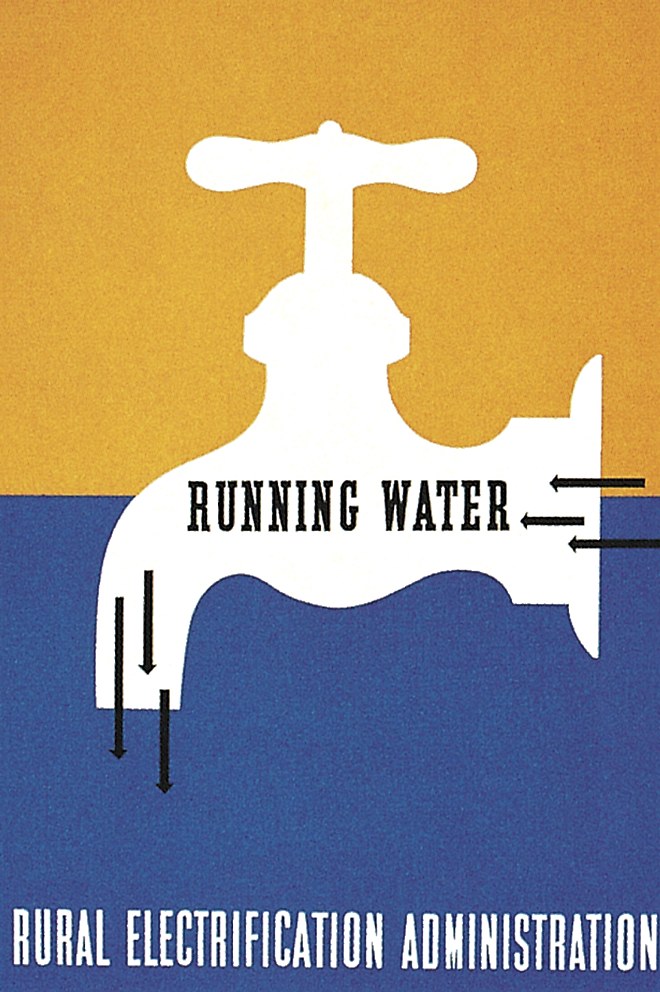

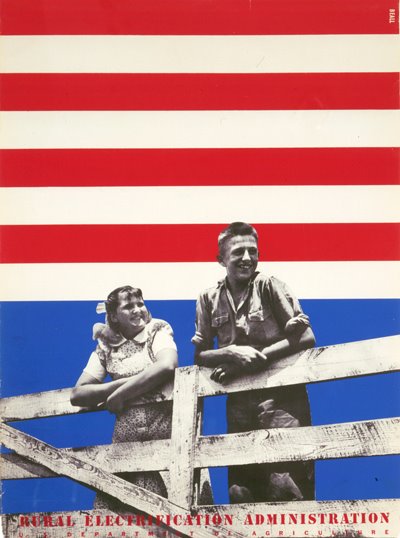

Chicago was the crucible of Beall’s early development. In 1935 he moved to New York, whose tradition of modern art and design offered a stimulating climate of ideas and sophisticated exchange. In 1937 he designed a complete series of educational and informational posters for the Rural Electrification Administration, a New Deal agency. These posters incorporated new visual ideas developed by Paul Klee,Herbert Bayer, Kurt Schwitters,Jan Tschicholdand others of the vanguard European schools.

By then, Beall had thoroughly assimilated these ideas so that they provided only the remote background to his own personal American idiom. Public and professional reaction to his work was immediate and completely enthusiastic. The spectator was instantly gripped by his excitingly different graphic composition. It was an unconventional design rhetoric employing contrast and incongruity, scale, bold abstract shapes, thrusting perspective, a shocking introduction of punctuation marks and typographic devices. If the cast was diverse, the plot was sure and the direction disciplined. Each poster delivered an arresting message. Quickly recognized for its contribution to contemporary graphic design, Beall’s work was exhibited in 1937 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Beall demonstrated with these posters that the language of communication was not necessarily bound to timeworn clichs and literal conventions. An expanding world of science, technology, and manufacturing had brought about rising expectations that called for a new graphic imagery, succinct of statement and visually attuned to the increasing velocity of American life. Industry and commerce, normally slow to respond to rapid changes in the forms of communication, were uncommonly quick to recognize Beall as a pacemaker. His special intelligence and unique concepts were vital to the ramified communication needs of modern industry. Like all great designers, Beall did not try to impose a fixed style on each problem. If there was a Beall imprint, it was the mark of his personality and aesthetic philosophy.

Beall recognized the tenacity of stylistic manner and cautioned that the designer, to remain vital and persuasive, must keep his defenses up. Speaking about this problem, he said, “Every designer is obviously constantly in contact with various and numerous pressures as well as influences. If he has built up over a period of years a background of sources that are truly inspirational although not directly within the field of his endeavor, and if he tries to maintain an objectivity toward each specific problem, he will more successfully form a bulwark against these influences.”

It would have been immensely out of character for Beall, a most cosmopolitan man, to suggest that the designer be indifferent to the surrounding world of design or to build an ideological moat around himself. He further suggested “that specific inspiration be derived from somewhat allied but nevertheless basically remote areas.”

Beall worked in New York City until 1951, designing a prodigious range of material in all forms of graphic communicationpackages, ads, booklets, corporate identity problems, and exhibitions. After 1951, acknowledging that “the creative atmosphere is not the same for all men,” Beall sought the tranquility of his home and farm in Connecticut, fearful, one suspects, that he would fall victim to the very dangers he cautioned against. This was neither retirement nor isolation, for Beall established his complete design studio in this new environment. He did, as he said at the time, “learn to see rather than just look at things. This is a never-ending process which the dedicated artist must teach himself.” Removing himself from the swirling turbulence of New York did not lessen Beall’s inventiveness or his productivity. He continued to create and design with his customary urbanity and insight. Some of his lasting achievements in corporate design were for Chance Vought, International Paper, and Western Gypsum. Fulfilling his own adage, “The very way a man lives is directly akin to his work,” he remained a maverick until his untimely death in 1969 at the age of sixty-six.

In the galaxy of the American graphic design, Lester Beall holds a special position. He remains for us a pioneer, one of the experimental visionaries who joined the links of our chain of knowledge. He saw farther and more daringly at a time when his contemporaries looked and saw not.

Fifteen years ago, Lester Beall spoke at a conference. One of his observations then epitomizes the man and the enduring spirit of his testament: “As graphic designers of today’s printed page, long dependent upon means of communication, we should envision ourselves as the inevitable architects of future revolutionary systems of communication.”