Howard Gossage

1970 Creative Hall of Fame Inductee

Advertising, Design, Illustration

Howard Gossage, a legendary copywriter, transformed advertising by making it about life and creativity rather than mere sales. His innovative approach inspired many, including Jeff Goodby, who admired Gossage's ability to blend art with advertising, encouraging a fun, engaging perspective that liberated the industry from self-loathing.

Career

A few words on Howard Gossage by Jeff Goodby

Actually, out of all the people I’ve never met in my life, I feel I know Howard the best. I sort of triangulated him back to life from meeting a lot of you, like a planet you can’t see but you know it’s there because you see the effect it has on the paths of the things around it.

I’ve told the story many times, but it’s worth telling again. In 1980, when I was working for Hal Riney in San Francisco, he gave Rich Silverstein, Andy Berlin, and myself the job of writing the San Francisco Advertising Club’s creative show. We decided to name a copywriting award after some famous San Francisco copywriter, so we started asking people who the right person for that might be. We were determined not to use Riney, because that was too…obvious. And we weren’t into obvious.

One name kept coming up. This Gossage guy. We’d never heard of him. “His old partners, Bob Freeman and Marget Larsen, are still in business,” someone said. “They’re over on Vallejo Street somewhere.” On a foggy afternoon, Berlin and I went over there and knocked on the door.

“Wait. Tell me what you want again,” Marget said through a crack in the door. We stammered out why we were there and, amazingly, she let us in. Freeman was there, a startling presence. I referred to him somewhere in writing as “soupboned,” but looking back, his bones wouldn’t have made all that much soup. He was more like a human-sized preying mantis. Marget was gorgeous, even at — what? — sixty something. I think that was why we really wanted to get inside the door that day. I remember watching her bend gracefully over some fabric she was designing for Stanford University. We were totally in love.

We spent three hours with Larsen and Freeman. They’d never seen us in their lives. Three hours. Howard had that kind of effect on things.

That afternoon, I probably heard 60 per cent of all the Gossage stories anyone knows anywhere. They were enchanting stories, told many times to me later by others, with the details slightly altered for effect, like legends told around an Anasazi campfire.

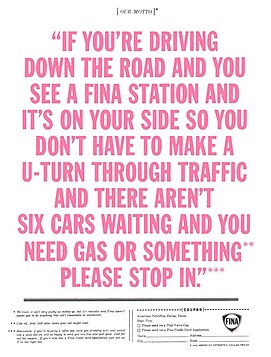

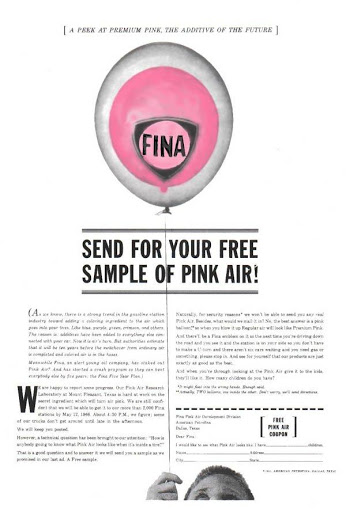

When Berlin and I got outside, we looked at each other like Moe and Curly must have looked at each other when they first met Larry. This Gossage guy was a spiritual double-oh-seven license to kill. Instead of pushing endlessly against the dreary resistance of creating advertising that sold stuff, he made advertising about advertising, advertising that was written from the larger perspective of capital-L life. From the perspective of people whose eyes were open and who told the truth because it was the most disarming of all selling tools.

He was dangerous. We loved it.

Howard’s enlarging of the playing field was quite different from the thing Riney did. Hal asked people to reconnect with some inner sense of integrity and trust, a structure that was inside all of us, embodied, he said, in the towering figure of the western cowboy. Howard, on the other hand, was all about convincing the cowboy to play strip poker, beating him, and then laughing as he gave him his clothes back.

If you’re an advertising person, this is powerful stuff. When Goodby, Berlin & Silverstein was opened in 1983, we ran an ad with Howard’s picture and the headline: “An advertising agency founded by a man who’s been dead for 14 years.” Gossage was the plastic guy on our dashboard and we were out there hitting the gas in his honor.

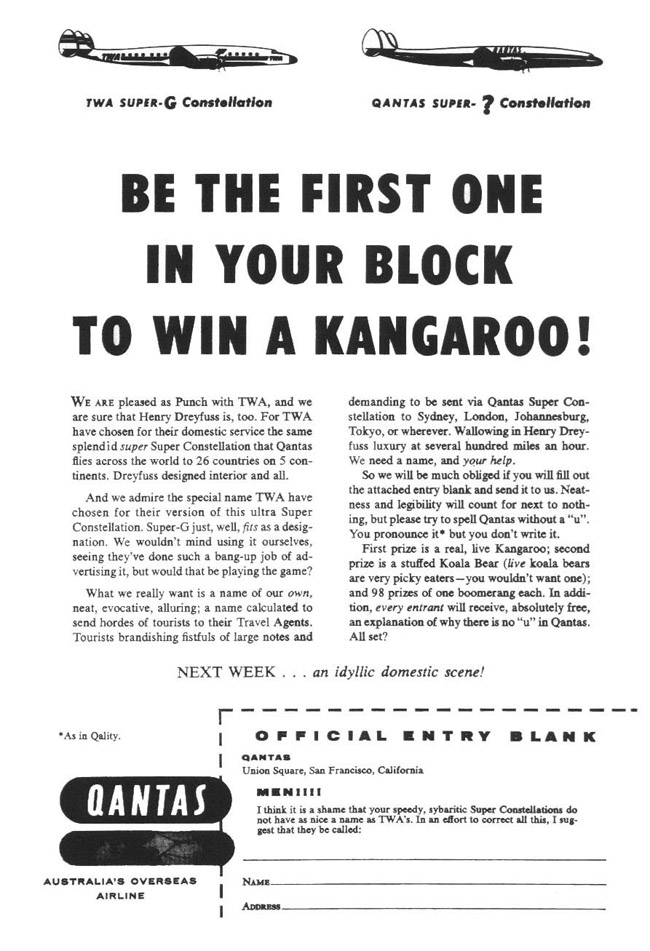

We immediately tried to emulate the terrific ironies of Howard’s campaigns for Eagle Shirtmakers and Qantas. And of course failed to measure up. Another of Howard’s lessons was to find your own damn way of looking at the world.

Along the way, however, we hit upon a number of campaigns that I’m sure were heavily influenced by his quiet creative direction.

For instance, we worked for a chain of Mexican restaurants called Chevys that prided itself on making food fresh each day. So we decided to make our TV commercials fresh each day, shooting them at dawn, editing them all morning, running them in the evening, and tossing them out. He would have liked that one.

And time and again over the years, we’ve totally ripped off one of Howard’s most persistent tricks: Asking the audience to write the ads for us. It’s a great strategy, telling the customer that we have some big dilemma, asking them to write in as to what we should do about it, then running the responses as ads. We did this for Polaroid and Nike and eBay. Very cagey stuff. And extremely easy on copywriting costs.

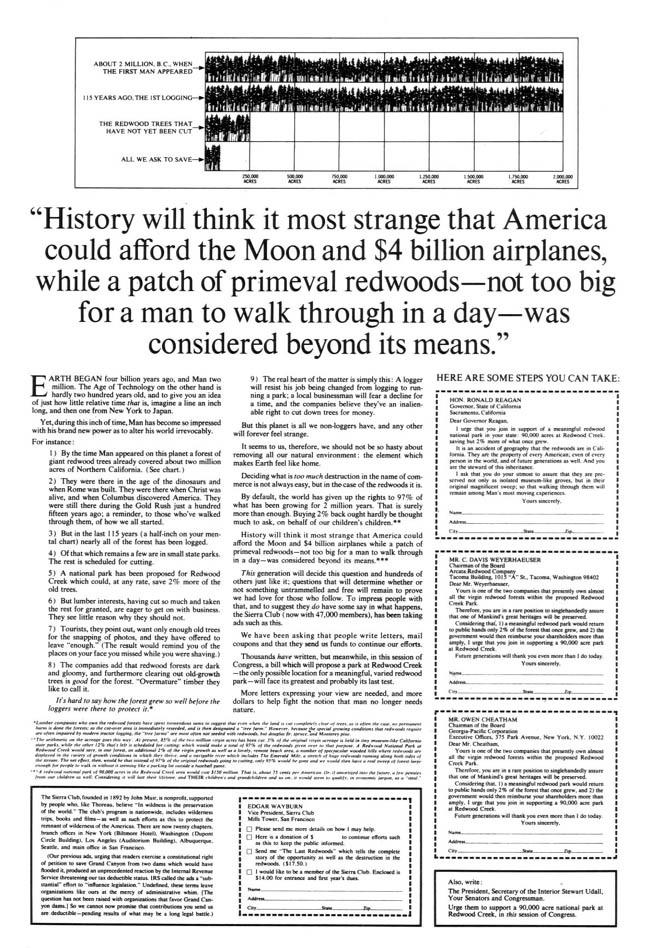

These were ideas that transcended selling, transcended business, and asked people to think about life, in a larger sense. And certainly a lot has been written, even by me, about Howard’s ability to do this. He made advertising art — which it can be, it’s not too big a word, despite what David Ogilvy always said. It turns out that the word “art” has roots similar to “artifice” and “artisan” and actually suggests something done to create an certain effect or have a specific influence. And that’s no doubt how Howard thought about this work. It was like lighting cherry bombs. He was always there, saying “Watch this.”

But in a funny, more down-to-earth way, Gossage was also a realist. Advertising, day-to-day, is a hard business. A business of rejection, often carried out by people you have little respect for, cultural death robots who happen to have a lot of money. Howard was great at this business because he projected a feeling that he was having more fun than you were and would continue to have it whether you came along or not. This was incredibly attractive to even the dumbest among us.

By acting this way, like Dorothy going to the Wizard, Howard liberated the advertising world from its endless circle of self-loathing. He responded to the self-loathing of advertising people by letting it out of the closet and embracing it as a kind of toxic creative spark.

I thank him every day for it. And I thank Marget Larson for opening that door.