Hal Riney

1994 Creative Hall of Fame Inductee

Advertising, Design, Illustration, Education

Hal Riney, a prominent advertising figure, revolutionized the industry with memorable campaigns for brands like BMW, Gallo wines, and Bartles & Jaymes. His work, characterized by creativity and impact, influenced American culture and politics, including the famous "It's Morning in America" campaign. Riney's legacy continues to shape advertising today.

Career

It was just eleven and a half years ago, during the summer of 1982. I was at Ammirati & Puris and we were looking for a new voice for BMW.

I’d heard a voice that I liked a lot on a campaign for Gallo wines, and since an old friend of mine worked at Ogilvy & Mather in San Francisco, I gave her a call to see if she knew who it was. “Oh, that’s the guy who wrote the spots,” she said. “As a matter of fact, he heads up the office here. His name is Hal Riney.”

I asked her how to spell it. It was the first time I’d ever heard the name.

My ignorance, I think, was typical of the New York advertising community in the early eighties. Soon, though, the ignorance and the bliss that it brings would end. Within a year or so, people like Hal Riney, Lee Clow and others would begin cleaning our collective clocks, first at the awards shows and later, in major new business pitches. Oh, they had done some great work already, lots of it in fact. But we were snoozing at the wheel, and by the time we woke up we were looking at their tail lights.

For quite a while thereafter, it seemed that whatever good work the industry would do, Riney would find a way to do something better.

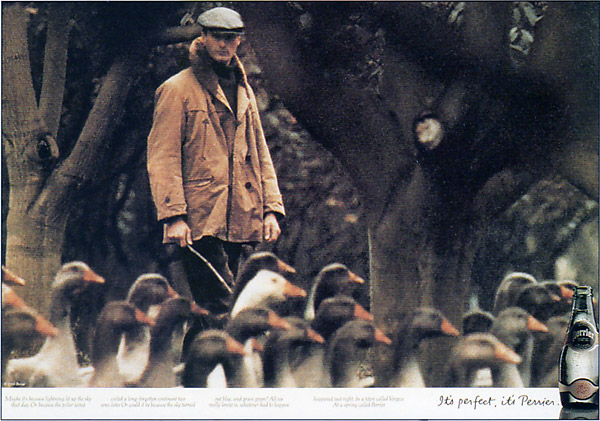

We’d see a new campaign for Perrier so artfully written and executed it made us forget how good Earth’s First Soft Drink had been. Someone would write a great campaign for California Coolers. Hal would create a product called Bartles & Jaymes (he found the names in a telephone directory) and then write a campaign featuring two of the more memorable characters ever to grace our television screens.

Along the way we’d see great commercial after great commercial for Gallo wines, a client for whom it had been said good work could not be done. In the effortless manner that characterizes his work, Hal would persuade America to believe that Gallo, a wine usually associated with brown paper bags, was a pretty good table wine. A feat tantamount to Bill Bernbach convincing us that a funny little car called the Beetle was the intelligent choice.

Advertising folklore has it that Ernest Gallo once said, “An agency is like a grape. You squeeze it dry and then you throw away the pulp.” Whether Ernest truly made that statement is beyond me. What is true is that Hal’s juices never stopped flowing.

In fact, it could be argued that Hal has written and (or) art directed more commercials than anyone else in history. Doubtful? Consider this. There were one hundred fifty-three commercials in the Bartles & Jaymes campaign. Hal wrote every one of them. To equal his output on that account alone, a writer would have to produce a spot every month for the next twelve years or so.

Obviously, it’s not the quantity of work that’s most important. Sometimes it’s not even the quality. It’s the gravity. In whatever spare moments Hal found between writing commercials and building an agency, he created work that would have a more profound impact on people’s lives.

In 1969, he co-produced a documentary on retarded children called “Somebody Waiting.” He and his fellow author were nominated for an Oscar.

In 1984, he helped elect a President. No matter which way you cast your ballot that year, you had to acknowledge that “It’s Morning in America” influenced the way millions of other Americans cast theirs.

On a lighter note, somewhere along the line Hal also commissioned a then-young composer named Paul Williams to write a tune for a California bank. To my knowledge, the resulting song, “We’ve Only Just Begun,” is the only advertising tune ever to become the number-one hit in the country.

Hall-of-Famers are held to a higher standard. They are measured not merely by what they have penned, but by what impact they’ve had on the business at large.

Let’s start close to home. With Goodby, Silverstein & Partners, Mandelbaum Mooney Ashley, Citron Haligman Bedecarre, as well as the West Coast offices of some larger enterprises, San Francisco is sort of a hot advertising town these days. Yet it’s fair to say that, at best, it might be lukewarm here without Hal. Not only did the principals of many of these agencies once work for him, many left other cities to do so. The large pool of talent, as well as the high standard of work in San Francisco exists, in some part, because of Hal Riney.

On a national scale, Hal has not only become a name in the business, he has become an adjective. We find ourselves referring to certain commercials as Riney-esque. We ask for Riney-like voice-overs. Recently, a rather well-known announcer asked me to thank Hal for giving a brand name to what he does, which happens to be Hal-like readings.

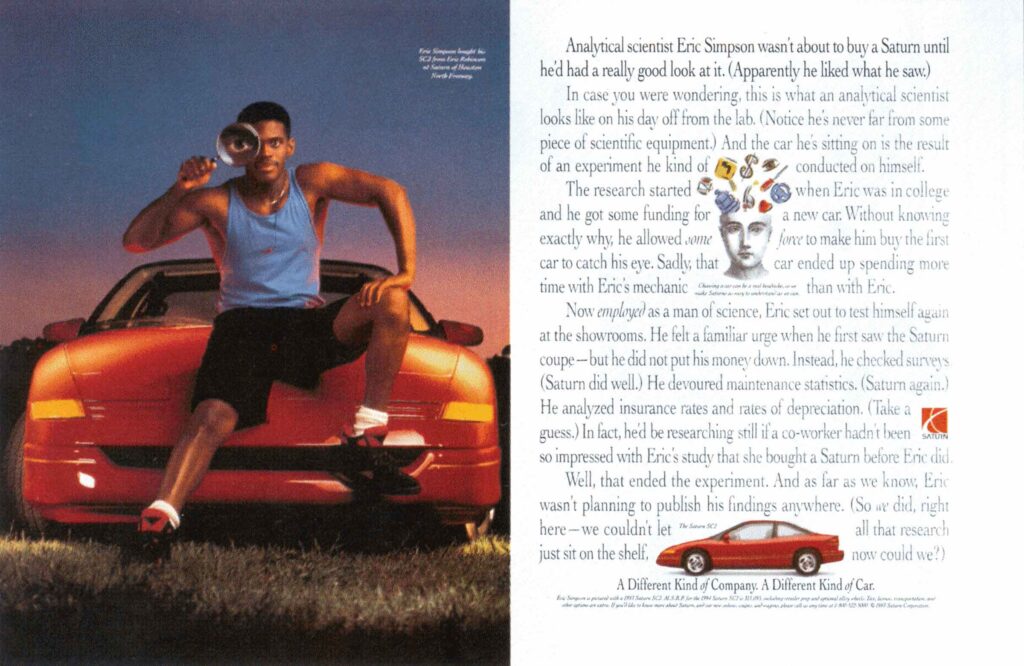

It’s been a pretty good year for Hal. In 1993 the Saturn campaign which he has so deftly guided is helping to sell every car that company can produce. He’s currently putting the finishing touches on a ninety second Alamo commercial he created for this year’s Super Bowl. His shop has been named Agency of the Year. He has been inducted into the Creative Hall of Fame.

And it’s only the end of November.

When I was requested to write this piece, I asked Hal to please jot down a few notes about himself. He did. Undoubtedly, it was the dullest piece of writing he’d done in his career.

It seems the only thing he doesn’t do very well is brag.

Which is another reason why most of us are still unfamiliar with the greater body of Hal’s work. Campaigns for Yamaha motorcycles and Henry Weinhard beer, among others. Work that was done long before his name went on the door, before his voice went on the air, before we realized that Madison Avenue had emulated Route 80 and headed west.