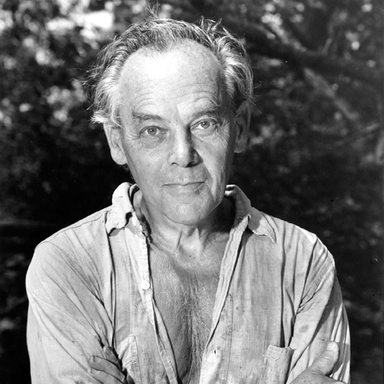

Gy Kepes

1981 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Design, Education, Illustration, Advertising, Photography

Gyrgy Kepes (1906-2001) was a Hungarian artist, educator, and designer who influenced modern art and design. He established the Center for Advanced Visual Studies at MIT, blending art and science. His works reflect nature's impact, and he is celebrated for his teaching and innovative contributions to visual design.

Career

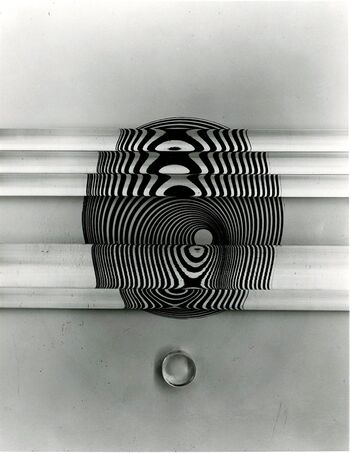

In 1949 Gyrgy Kepes moved into his house and studio on Long Pond Road in Wellfleet, Massachusetts on the northwest hook of Cape Cod. The house was designed by Marcel Breuer, an old friend from his days in Hungary. An early visitor to the site observed the gulls circling over the great stretches of sand and dune grass and remarked that this proximity to nature would be a great source of inspiration to the artist. A viewer of his paintings immediately sees the influence of nature on the artist, for they are layered with an insight and experience and spell out, in the words of one critic, “Like the rings of a tree, what words cannot adequately display.”

There have been many influences on the life and career of this painter, sculptor, filmmaker, planner, designer, writer, and educator, and Gyrgy Kepes has, in turn, touched hundreds through his teaching and countless more through the impact of his design.

The road to Massachusetts has been long and circuitous, leading from Budapest through Berlin and London to Chicago, from Chicago to Texas and Brooklyn and ultimately to Cambridge.

Along the way his works have found their way into galleries and art museums and private collections in San Francisco and Florence, New York and Rome, Dallas and Budapest, Boston and Berlin, Montreal and Vienna and in a score of other major cities around the world. Kepes was to find himself a member of that small army of migrs who left Europe between the wars to settle and work in the United States and, through their efforts here, found international fame, acclaim and influence.

Gyrgy Kepes was born in Hungary in 1906. In 1924 he entered Budapest’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied with Istvan Csok Hungary until 1928. The Academy at the time was a hotbed of both political and artistic activity, and Kepes affirms that he became influenced by the revolutionary poet and editor, Lajos Kassak. He gave up painting for a while, turning to filmmaking, which he felt was a better medium for the artist to express his social beliefs. “In the 20’s,” he once explained, “I became deeply disturbed by social injustices, particularly by the inhuman conditions of the Hungarian peasantry.” Clearly the maturing new art form would provide a platform to expose social inequities. In 1930, he wrote toLszl Moholy-Nagy, who had written for Kassak’s quarterlies and so a link existed between the two. This was the same year that “The Blue Angel” and “All Quiet on the Western Front” were released, when motion pictures were becoming an international force. Nagy invited Kepes to join him and they worked together on and off until 1937, first in Berlin and later in London. In Berlin he met Walter Gropius, among others; in London, through science writer J. J. Crowther, he came to know a large number of eminent British scientists. At the same time his interest in John Ruskin and William Morris was rekindled and his own view of the artist’s role as a transformer of the environment reinforced.

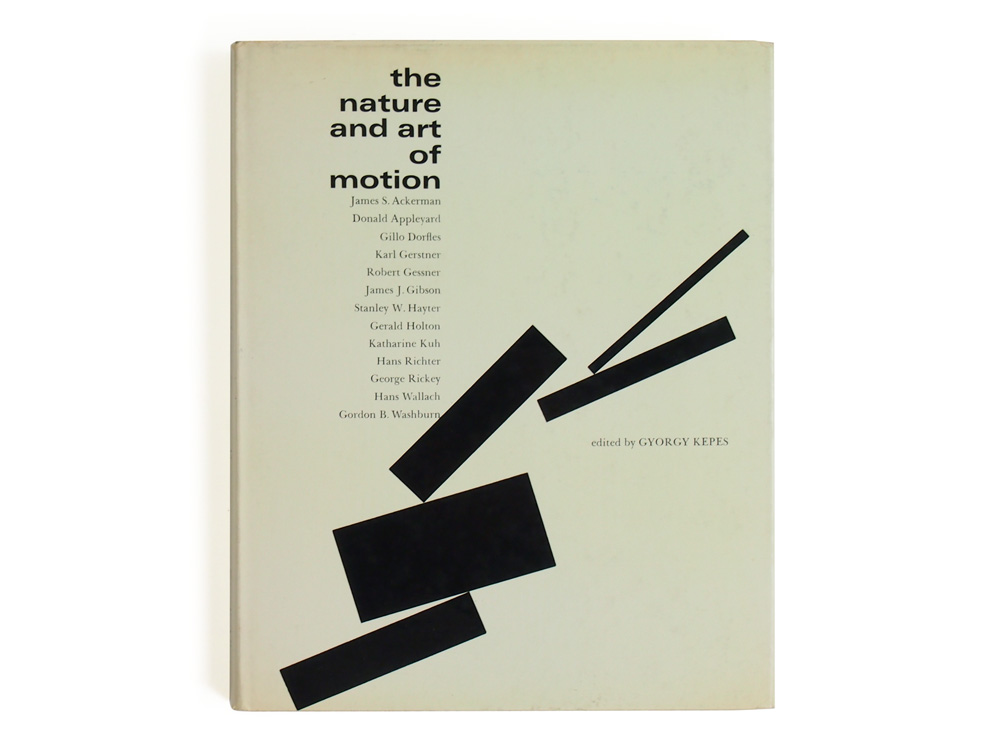

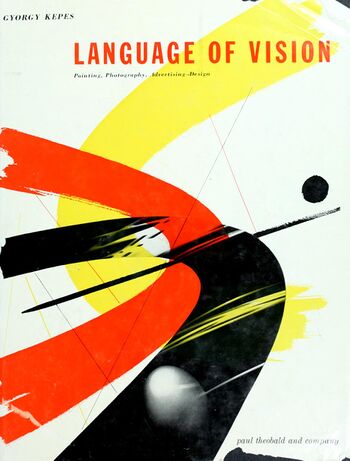

The Nagy connection was to have greater import than Kepes ever dreamed. In 1937, Nagy was invited to establish a New Bauhaus in Chicago and he invited Kepes to join him there to found a light and color department, the first of its kind in the United States. Later in January of 1942, fifty people, many of whom worked at the Chicago Institute of Design (now the restructured New Bauhaus), were asked to study Army and civilian camouflage by the U.S. Army. “I became newly alert to the urban environment by looking at camouflage from the air, at what light patterns could do,” he recalls. This research gave him an opportunity to enlarge his visions of the potentialities of environmental art and in 1944 his now classic, “The Language of Vision,” was published.

The following year Kepes was invited to establish a program in visual design at the School of Architecture and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In his early M.I.T. years, Norbert Wiener was developing his cybernetic theories, which were to usher in the era of the computer, and contact with Wiener brought to Kepes another important “inner revolution.” This led to his writing “The New Landscape in Art and Science,” perhaps his most important work.

Kepes’ plans began to take form for his Center for Advanced Visual Studies at M.I.T., ideas that took root in 1960 and which were approved seven years later. The Center was to be a facility for the “creative use of light on a grand scale,” a setting where artists and scientists could collaborate as they experimented with new media toward the end of using art to transform our environment, Kepes’ goal.

As for his relationship with art directors, it is a long one, going back to 1939 when he conducted courses for the Art Directors Club in Chicago. He was one of the first art directors asked to create ads for the Container Corporation’s program. He designed “The Art of the United Nations” exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago and also did graphic designs forFortune Magazinein the forties. In 1949, he created the outdoor mural for the Fitchburg Youth Library in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, and designed a children’s room to stimulate sensory participation with the environment with his wife, Juliet, as his collaborator. Never afraid of the commercial world, the following year he designed the first kinetic outdoor light mural for Radio Shack in Boston.

Of his principles of graphic design Kepes has said: “Design which has its root in the heart of man and not in his pocket is aliveno genuine work is done if the intent is shallow. My whole life has been a struggle to make design a part of the human lotnot to sell but to help life.” To Gyrgy Kepes, even a poster should serve a double purpose. “One is to advertise the product, the other to train the eye.” These are very high ideals, and in the context of his life, he has succeeded in this as few have.

Even after his return to painting in 1951 he continued with his design work, working in the publishing field with graphic design assignments for Beacon Press, theAtlantic Monthlyand Little, Brown. As the 50’s decade was coming to a close, Kepes was designing mosaic murals for the Sheraton Corporation in Dallas, Houston, Chicago and elsewhere and was also designing the programmed light mural for the KLM office in New York City. Always on the lookout for new areas of graphic creativity, in the sixties he designed the mosaic mural and glass windows for Temple Emanuel in Dallas and the faceted glass windows for Saint Mary’s Cathedral in San Francisco. Since then his career as an educator has taken him to Hawaii, Florence, Bogot, Columbia, New Orleans, Rome, Salt Lake City, Houston, Dartmouth College and Washington University in St. Louis.

Today, more and more of his time is devoted to painting, canvases which are about relatedness and complementaries, about the dialectic between nature and artifact, between images of order and chaos. Kepes himself talks in terms of the Greek myths of Daedelus and Antaeus, the one with his attempt at soaring flight, the other with his feet firmly on the soil of the earth mother.

This year finds Gyrgy Kepes a visiting professor of art at the Rochester Institute of Technology. Kepes sees himself as striving with “a scientists brain, a poet’s heart and a painter’s eyes” to solve the riddle of man’s place in the cosmos. How others view his contributions to life in our time may best be summed up in the words of designerSaul Bass: “He changed my life. He turned me around and I became a designer because of him. He opened the door for me that caused me to understand design and art in another way. He is a truly inspired teacher. It is rare that a man can be both an artist and a teacher and perform superbly as both.”