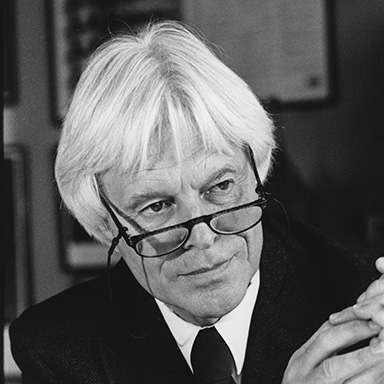

David Abbott

2001 Creative Hall of Fame Inductee

Advertising, Design, Illustration, Education

David Abbott was a pioneering British advertising writer known for transforming Sainsbury's marketing by treating women shoppers as intelligent consumers. He co-founded Abbott Mead Vickers, the UK's top agency, emphasizing creativity and respect for the audience. His legacy is marked by intelligence and humanity in advertising.

Career

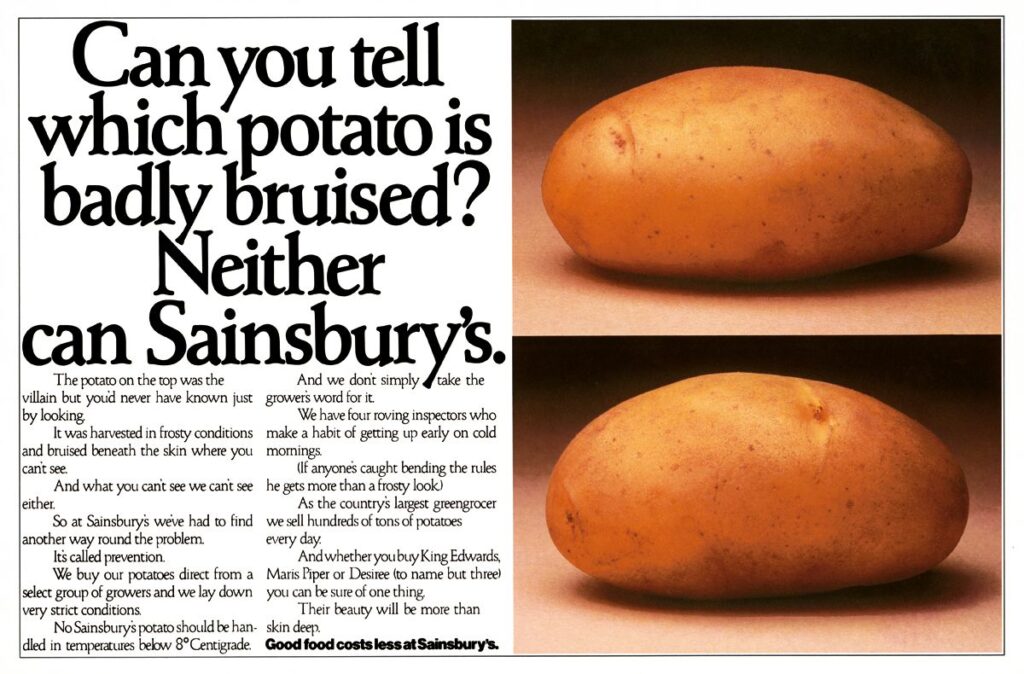

When I think of David Abbott, I think of mince beef or potatoes or some other rather prosaic foodstuff. This is not a reference to his visual appearance, which, as it happens, is dapper to the point of perfection. No, it is the produce featured in ads written by David for Sainsbury’s, a brand that he helped build into the biggest, most well-regarded supermarket chain in the country.

The Sainsbury’s campaign was the first in a category characterized by dull yet insistent ads, which treated women shoppers as human beings with brains in their heads-people who cared about what they bought, even, my God, considered it important in their lives.

Prior to David’s campaign, price ruled. Why? Because research said that women only ever used price as a reason to trudge to one shop rather than another. Research may have spoken but David Abbott’s instincts begged to differ.

What followed was a significant piece of UK advertising history and very quickly became a lesson to everyone in advertising wherever they lived.

Know your product, respect your audience, trust your intuition. Watch how people buy things, even listen if you can. By all means think about their deep-seated motivations but don’t get entwined in them. Treat your audience as you would like to be treated.

These rules are regularly spouted by so-called leaders of the advertising industry. Very few of these titans believe in them, particularly in the face of a demanding client or a repitch. Even fewer live by them and build a highly successful agency in the process.

David Abbott is one of them.

But how did he manage to succeed where so many have failed? What qualities did he possess which allowed him to dignify this often undignified business?

First and foremost David is a great advertising writer, a definition substantiated by reams of work spanning four decades, all of which bores the indelible stamp of an intelligent and enquiring mind.

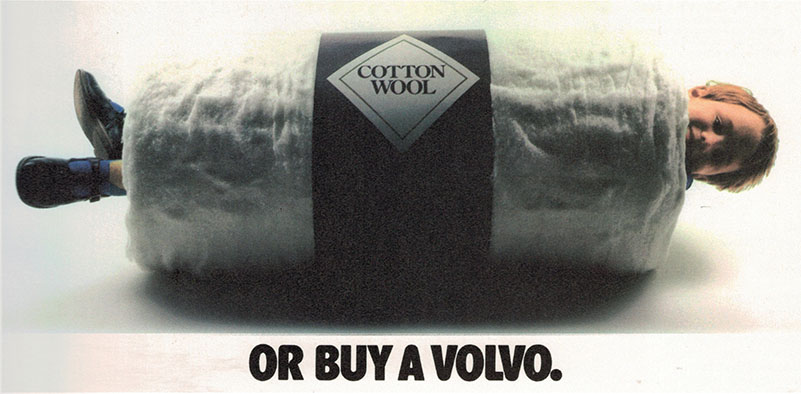

His British Volkswagon ads, created at DDB London in the late 60s, lived with the best of that remarkable campaign. His later work for Volvo, “The Economist” and the RSPCA all displayed his almost unique ability to create ads which were always ‘appropriate;’ never gratuitous in their use of eye-catching headlines or visuals and where the product was invariably king.

Undoubtedly his most enduring achievement is the agency he created with Peter Mead and Adrian Vickers. During the glitzy, and in the end, rather shabby, 80s, the advertising industry in the UK flattered itself that it was at the very hub of commercial and political life. Admen and women inveigled their way onto the high table and bragged about it, although they were less forthcoming about their actual contributions.

Quietly, and following an altogether different tack, Abbott Mead Vickers stole past their flash and faintly ridiculous competitors to become the No. 1 agency in the third most important advertising market in the world. No takeovers. No knighthoods. No PR-obsessed antics in an attempt to spin their way to dominance.

AMV not only became the biggest agency, it was the only agency to have been led to that position by a creative person: David Abbott. And though his partners were always on hand and contributed greatly to the agency’s success, AMV was always known as ‘David’s agency.’

This is his most important legacy.

Many creative people can write great campaigns, some can run terrific departments. But to turn those skills into a business, to be disciplined and commercial on behalf of staff and clients alike indicates qualities rarely, if ever, attributed to anyone in a creative department.

What was achieved at AMV has only happened at a handful of agencies in the history of modern advertising. It should inspire art directors and copywriters everywhere. It should teach them not to hide behind the wall of cynicism about clients’ lack of understanding or appreciation. It should encourage them to put their own heads about the parapet, in the belief that their skills and insights, their unusual almost quirky talent for mass communication could create an agency that one day may be as good as the agency David built.

In another and much more eloquent eulogy to David’s career than this one, Tony Brignull suggested that while many copywriters claimed the blood of Bill Bernbach ran in their veins, only David Abbott would pass a blood test.

If DDB taught us all what advertising could be, David Abbott and AMV accepted that baton with enthusiasm and ran with it.

David’s work stands, above all, for intelligence and humanity-rare qualities in a human being, let alone a transient piece of communication. And it is because he cajoled, argued, fought, charmed, probably engaged in hand to hand fighting to uphold those simple virtues, that his entry to The Creative Hall of Fame is so thoroughly deserved.