Rene Clarke

1972 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Advertising, Design, Illustration

Rene Clarke was a pioneering art director and artist who significantly influenced American advertising from 1912 to 1969. Known for his elegant and imaginative work, he received numerous accolades, including the Edward Bok medal. Clarke's dedication and integrity helped elevate the art director profession, leaving a lasting legacy.

Career

Art directors need not be told that they exercise considerable effect upon the far-flung levels of communication. This appraisal may not necessarily enjoy the condign public accord, but it is nonetheless demonstrably true. The art director, in our contemporary scheme of things, wields virtual daily power over what and how people see, hear, and, perhaps, think. Alas, the recognition of this influence has been slow in coming. For example, looking to the novel as a mirror of society, one would be hard put to think of any work that casts an art director as a central character. William Dean Howells, at the turn of the century, characterized one of the species in his book “A Hazard of New Fortunes,” but Howells’ creation would hardly be recognizable by current measurement, save the length of his hair. Lois Gould, a writer of contemporary vintage, creates an art director in her book, “Such Good Friends,” but she manages to keep the fellow in a coma throughout the entire story; moreover, he is entirely disreputable, foolish enough to have kept rather self-condemning notebooks. In less imaginative quarters, that respectable tome, Webster’s Biographical Dictionary, includes not one graphic designer or art director among its 40,000 names of noteworthy persons.

If the art director and the related makers of our visual culture have not received the appropriate professional esteem, it may be in some measure due to the youth of the profession. The Art Directors Club was founded just a shade over fifty years ago. A half-century may seem rather formidable to some, but in the broad hierarchy of professions, it is not a very long time. The club was formed, as most professional organizations are, to raise the standards of the profession and to promote the commonweal. Its first members were a group of artists cum art directors whose positions, with advertising agencies in most cases, required that they be practicing artists as well as caretakers of artistic style. Unhappily, the Art Directors Club lacked a permanent chronicler that would keep a running history of the youthful organization. We have, by good fortune, a rich oral history of the times, augmented by an imperishable record of achievement in the volumes of the Art Directors Annual. Of the hardy, farseeing band of founding members, the one name that appears regularly in these volumesfor good, if not overwhelming, reasonwas that of Rene Clarke, then an art director with the estimable agency of Calkins and Holden. Rene was the legally adopted name of James A. Clarke, who found much of his inspiration in the thought and work of Rene Vincent, a French artist who was both his colleague and mentor. Clarke came to Calkins and Holden in 1912 and remained there until 1956.

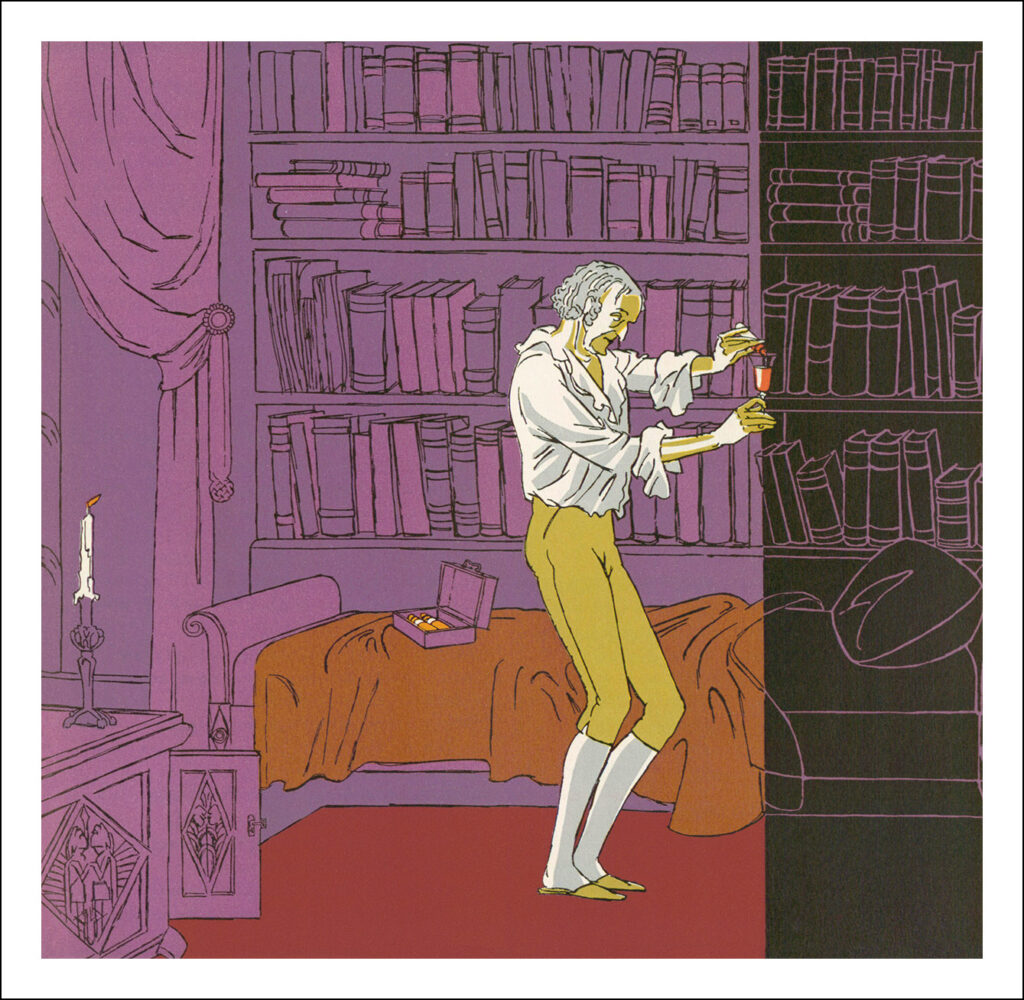

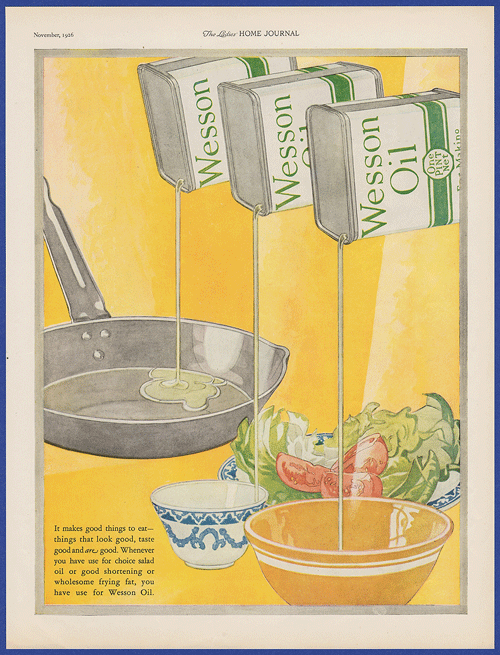

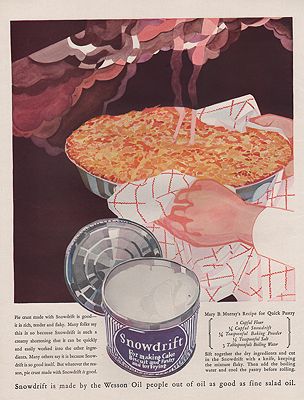

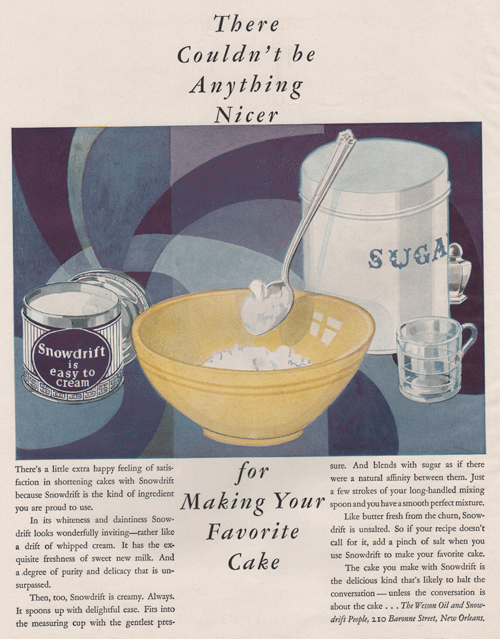

American advertising in the first decades of this century was, to say the least, conservative, almost inhibited in its lack of experimental vigor. American illustration was indentured to a realistic style, a meticulous depiction of objects that seemed to preclude any display of imagination. To be sure, the fragile linear influence of Aubrey Beardsley and his precursors were in evidence. But even that genre of illustration seemed to have its energy sapped by a rigid formality. In 1922, in the first Art Directors Annual, we find our eye regaled by the grace, imagination and versatility of Rene Clarke’s illustrations and ads. In this one issue, there is a linear, virtually gossamer drawing for a paper company ad, a bold allegorical illustration for an insurance company depicting the ravages of fire, and a strongly patterned elegant rendition of food for a salad oil producer. One is particularly struck by Clarke’s mastery when he manages to fit the cold mechanical shape of the salad oil container into the composition without a hint of aesthetic dissonance. In that series for Wesson Oil, there was none of our contemporary razzle-dazzle, no clever double-entendre designed to spur the mind. The ad stood or fell on the figure on center stage, and that was the subtle aesthetic wizardry of Rene Clarke. As the campaign continued, Clarke was actively engaged in working on illustrations and ads for a large number of products. Each of these introduced some special note that placed Clarke’s work distinctly above the visual platitudes of his era.

As the years progressed, Clarke clearly established his dominion over his subject and mtier. While the predominant stream of illustration languished in a non-controversial but stultifying literalism, Clarke’s work continued to take a new visual dimension. This was not the frenetic change of our era, but steady, modest, yet ineluctable extensions of the artist’s vision. A new lyricism evident in his work indicated that Clarke had begun to feel the transcendent effect of the paintings of Matisse, Klimt, Demuth, the vorticists and even the futurists. Clarke, the artist, was but one side of the man. He was also Clarke, the art director, responsible for both the stylistic direction and leadership at Calkins and Holden. Walter Geohegan, a former president of the Art Directors Club and colleague of Clarke’s, remembers Rene Clarke as an “aesthetically courageous” man, unselfish in his encouragement of subordinate artists and designers working with him. Geohegan recalls that Clarke was not given to petty rivalries and, on a number of occasions, would readily encourage conceptions for illustrations and ads at the expense of his own.

In 1928 Harvard University recognized Clarke’s unique contribution to American advertising. He was awarded their distinguished Edward Bok medal for having brought to the field a dignity and excellence that bespoke a respect for the American consumer. Clarke received comparable accolades from his peers. He was the recipient of at least four Art Directors Club gold medals and numerous awards of honorable mention for his extraordinary work.

Clarke’s work continued to retain its majestic elegance even as new visual devices and idioms began to assert themselves. Rene Clarke is not identified with one dramatic frisson, nor did he create a revolution of vision or thinking. He was the dedicated art director, the calmly inspired artist who brought a spirit of uplift to what man does.Paul Smith, one of the truly eminent figures of contemporary advertising, said of Clarke, “His work for Wesson Oil, Snowdrift, Rusling Wood, Hartford Fire, Red Black Starr Trust, Crane Paper, to name only a few, was head and shoulders above anything done at the time (or since, for that matter). He brought a fresh eye to the advertising business. And with E. E. Calkins (and their associates), he did much to raise the business to the status of a profession.”

Clarke worked well past the years that many even hope to live. He continued to paint, exhibit, and be the vital, ingratiating man he had always been until his death in 1969 at the illustrious age of 83. Clarke was much too modest a searcher ever to seek fame. He was nonetheless an important builder of his profession, one who gave it structure and purpose simply by his uncompromising integrity and the truthful beauty of what he did.