Paula Scher

1998 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Design, Typography, Illustration, Advertising, Education

Paula Scher, a prominent graphic designer, emerged in the 1970s New York design scene, creating iconic album covers and later establishing her identity at Pentagram. Known for her innovative use of typography, she has shaped visual branding for major clients, blending accessibility with artistic depth throughout her career.

Career

Paula Scher plunged into the New York design world in the early 1970s, a moment when progressive art directors, illustrators, and graphic designers, as well as architects and product designers, were drawing energy and ideas from the parking lots of Las Vegas, the Factory ofAndy Warhol, the creative boutiques of Madison Avenue, and the tragi-comedy of the Nixon Administration. This was the nadir of the Pop movement, a period when American design, music, fashion, and fast-food had become a global vocabularymore profoundly international than the International Style. From New York to London to Tokyo to LA, Helvetica was outpaced by the lascivious swashes ofHerb Lubalins lettering and the exuberant curves, serifs, in-lines, and outlines of a veritable harem of decorative typefaces revived from the dustbins of an ornamental past.

It was in this culture that Paula Scher came of age. She majored in illustration at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia, finishing her BFA in 1970. As a student, Scher avoided graphic design because she lacked the necessary neatness skills and didnt like arranging Helvetica on a grid. She didnt draw well either (a modest liability for an illustrator), but she discovered what she could do: come up with concepts and illustrate them with type.

In 1972, Scher jumped into the belly of popular culture; as art director for CBS Records in New York City, she designed approximately 150 album covers a year, and produced innumerable ads and posters. During her decade in the record industry (one year with Atlantic Records, the rest with CBS), Scher made work that was accessible but smart. She collaborated with illustrators and photographers to interpret music in suggestive, poetic waysshe preferred to invoke a mood or stage a mysterious scenario than provide literal depictions of bands and performers. Scher often drew on typographic styles from the past to complement the imagery she had commissioned. The economic crash that gripped the late 1970s pushed Scher to rely increasingly on letterforms over illustrations; the impulse to convey content and identity through typography became the hallmark of her mature work.

An enormous influence on Scher was designerSeymour Chwast, whose clever blending of image and type inspired countless students and young designers in the 1960s and 1970s. But Scher didn’t just admire Chwast, she married him. At age 22, she embarked on what would prove to be a long and complicated relationship with this towering hero of popular design, a man 17 years her senior. They later divorced, and Scher built a life and career on her own, pushing ahead in the competitive design world of New York to construct a distinct identity for herselfa difficult achievement for any designer, and a feat especially rare among women. She married Chwast again when she was 40, and today each enjoys the others hard-earned stature and independence, alongside their shared love and company.

Scher left CBS Records in 1982. She formed the studio Koppel & Scher with Terry Koppel in 1984, where she embraced the pressures of working on her own. The experience taught her the challenge of keeping her own clients and “paying [her] own phone bill, a situation distant from that of a corporation like CBS. In 1991, Scher became a partner in the New York office of Pentagram. This unique business environment makes each partner responsible for maintaining his or her own clients and design teams while sharing accounting services, overhead, and profits with the other partners. The sole woman among 15 partners, Scher describes herself as “the only girl on the football team. That doesnt make her a cheerleader or a trophy date, but an equal player in a pack of heavy-hitters. The Pentagram environment continually forces her to hold her own and stay on top, both creatively and economically.

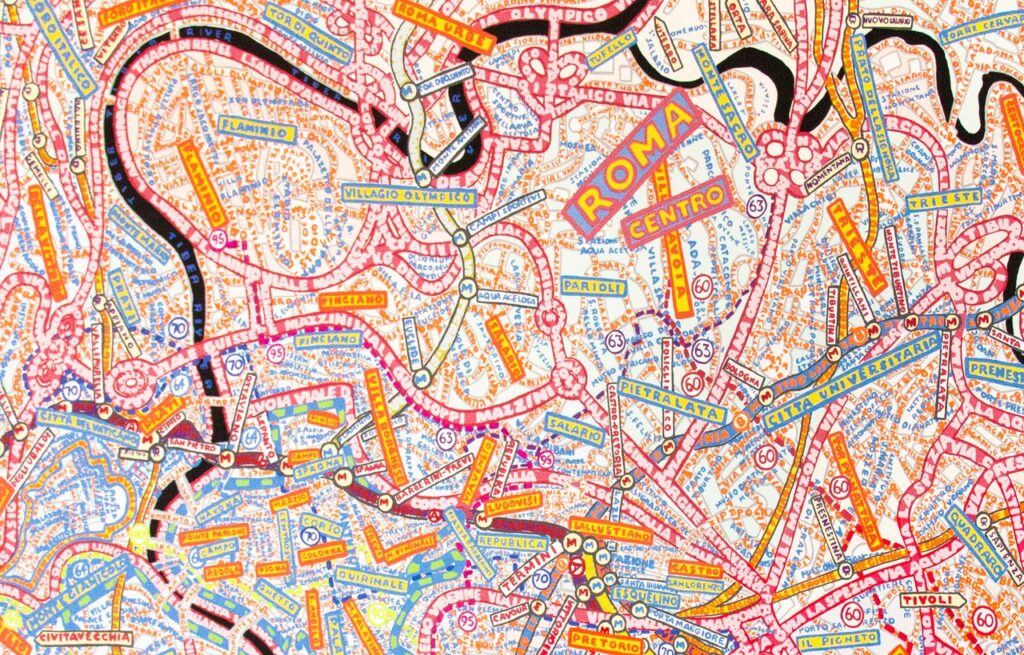

The move to Pentagram marked a major shift in Scher’s career. This world-class, large-scale studio brought Scher a new level of visibility, and cultural and economic clout. She now had access to clients and projects that would not have ordinarily come to a smaller studio, especially not to one run by a woman. The years at Pentagram have allowed Scher to sharpen her typographic wit and her knack for conceptual solutions into a powerful approach to identity and branding. Whereas Scher’s earlier work often centered around the creation of a neatly contained package for a specific cultural product, she now confronts the much broader challenge of conveying a visual personality across a range of media, from posters, advertisements, and packages to physical spaces.

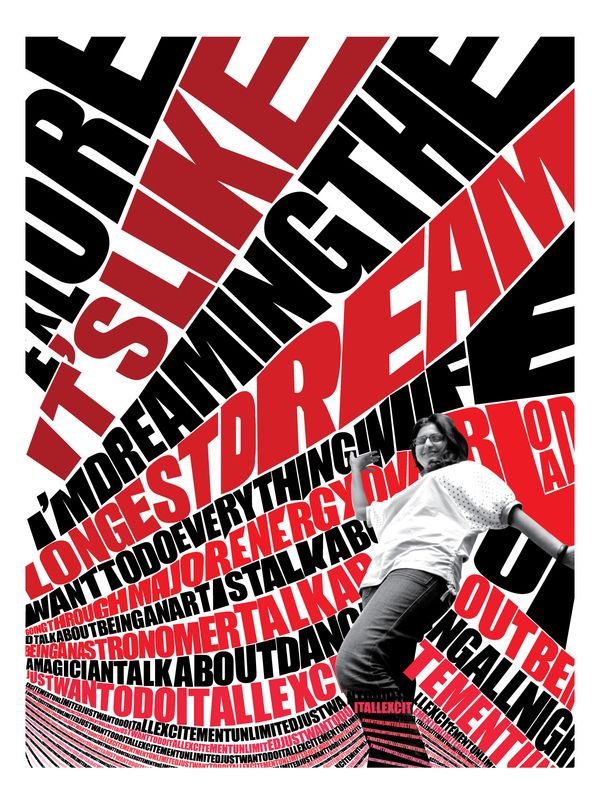

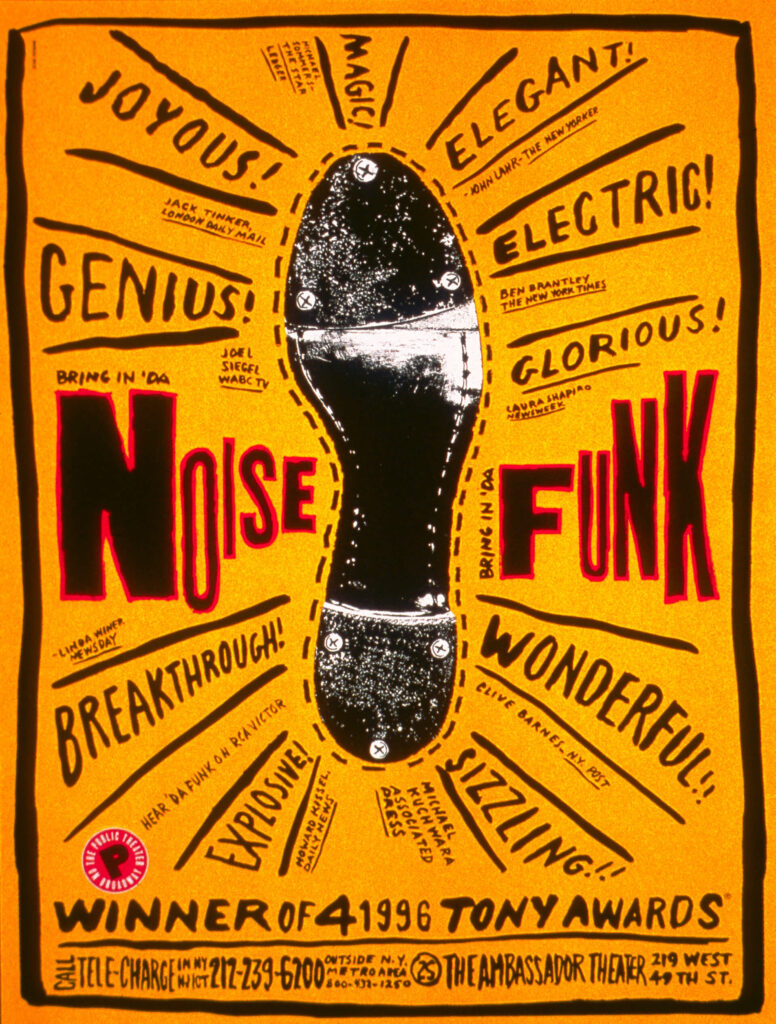

Among her most spectacular achievements has been the institutional identity she generated for the New York Public Theater in 1994. From large-scale billboards, down to the logo and stationery, Scher used a rhythmic mix of sans serif letterforms to construct a visual vocabulary that is both diverse and coherentlike the theater’s programming. Other clients includeThe New York Times Magazine, Champion International Corporation, Philips Van Heusen, and The American Museum of Natural History.

Assessing her work, Scher says, “I’ve always been what you would call a ‘pop’ designer. I wanted to make things that the public could relate to and understand, while raising expectations about what the ‘mainstream’ can be. My goal is not to be so above my audience that they can’t reach it. If I’m doing a cover for a record, I want to sell the record. I would rather be the Beatles than Philip Glass.”

Paula Scher is among the best designers of her generation. She cut a path for herself through the billboard-jungle of Pop, creating an approach to design that is articulate yet unpretentious, open to influences yet decisively individualistic. Through her astonishing visual work as well as her generous efforts within our profession as a teacher, advocate, and agitator, Scher has helped put an intelligent face on the field of graphic design.

-Ellen Lupton