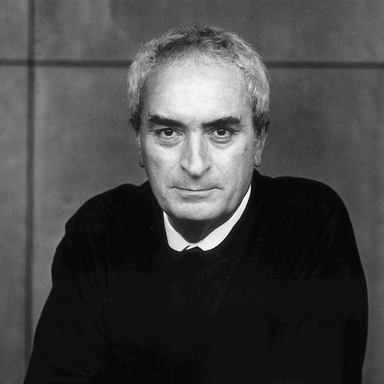

Massimo Vignelli

1982 ADC Hall of Fame Inductee

Design, Education, Typography, Advertising, Illustration

Massimo Vignelli, born in 1931 in Milan, is a renowned designer who, with his wife Leila, has influenced various design fields since moving to New York in 1965. Their work, celebrated globally, emphasizes elegance and innovation, earning numerous awards and transforming American graphic design, notably through the Helvetica typeface.

Career

Born in Milano in 1931, Massimo Vignellistudied architecture there and in Venice, and since then has worked with his wife Leila, an architect, in the field of designfrom graphics to products, from furniture to interiors.

Based in New York since 1965, their work has been exhibited throughout the world and is in the permanent collections of several museums.

Massimo Vignelli has taught and lectured on design in major cities and universities in the USA and abroad. Among their many awards: the 1973 Industrial Arts Medal of the American Institute of Architects, and an honorary doctorate from the Parsons School of Design, NY. Following is an excerpt, written by Emilio Ambasz, from the introduction of the catalogue of the exhibition at the Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea, Milan, Italy, 1980.

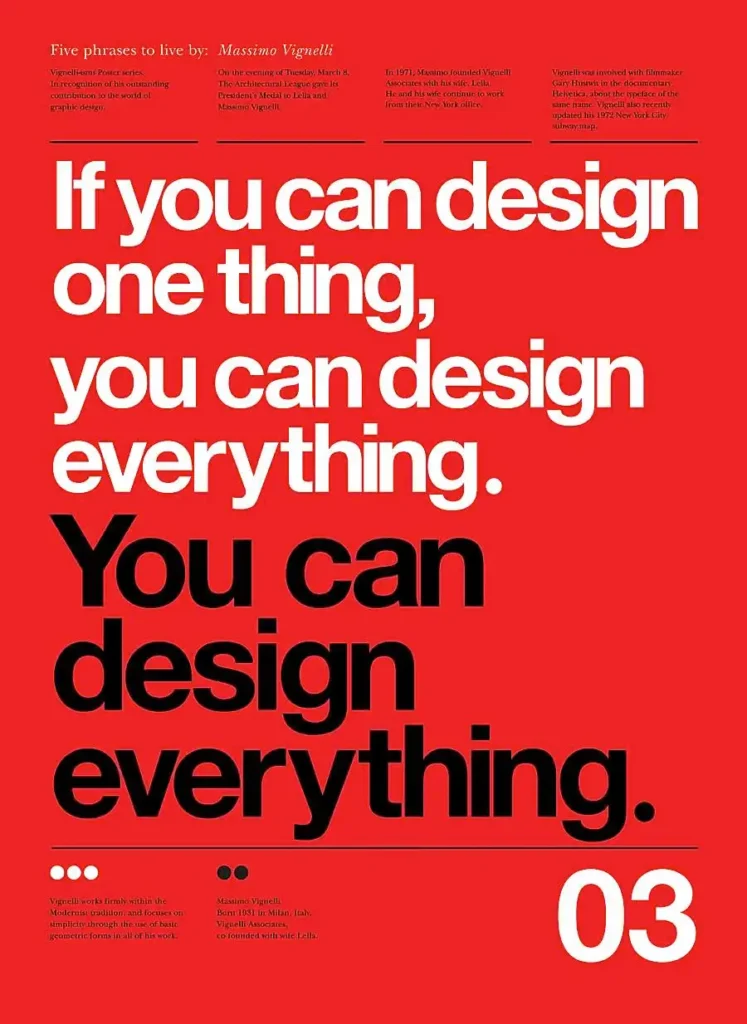

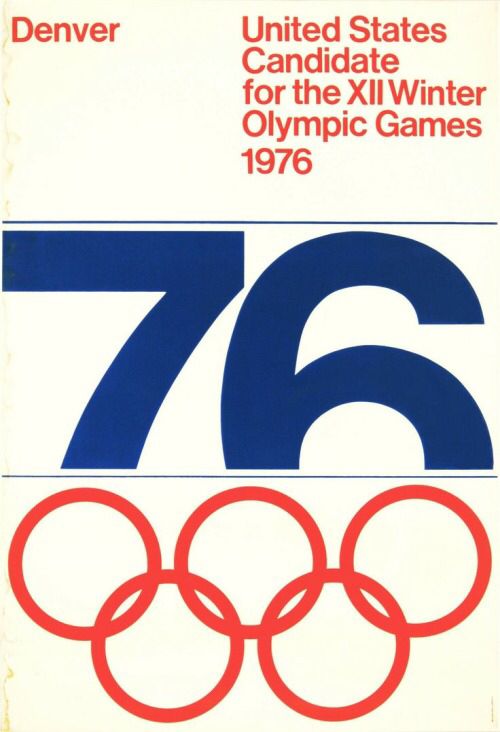

For years since 1964, they have been the ambassadors of European design; specifically, the standard-bearers of a Mediterranean brand of Swiss graphic design made more agile and graceful by the traditional Italian flair for absorbing and re-elaborating foreign influence. Almost single-handedly Massimo introduced and imposed Helvetica typeface throughout the vast two-dimensional landscape of corporate America.

His graphic design was always distinct and elegant and, if it is true that as time passed by it began to lose its crisp profile, this was due, in great part, to his having generously taught a whole generation of American designers how to evaluate, organize, and display visual information. By giving away his lucidly elaborated formulas he had allowed them to reproduce his image until it became so omnipresent that it began to become transparent.

There are great comforts in accepting the rewards of having developed an ineffable technique. And in America’s Eden, there are even greater rewards for such technical virtuosity, provided the exercises take you nowhere. It is to the Vignellis’ credit that they did not accept this situation. They have been searching for ways out of such deadening comforts. Admittedly, their probes were at first cautious, but theirs is not blind courage, but the lucid sort which presses ahead while fully aware of the risks awaiting. At a crossroads in their careers they valiantly march on. With one hand they hold onto the luminous treasures of their past experiences, while with the other they seek, sense, and try for the unknown, hoping for that which daring and risking may bring about.

Flashes of randomness have begun to appear in their work. An invitation to a New York showing of their work was sent to all their friends in the form of a crumpled piece of tissue paper. The paper’s color wastrs chicand the typeface of the most accurate elegance, but the controlled passion that crumpled piece of paper denoted could not be disguised behind its carefully rehearsed throw-away elegance. Massimo and Lella, the professionals par excellence, are now undergoing a subtle but deep transformation. The hand which once followed carefully laid-out patterns has still kept its elegant demeanor, but the gesture is now looser and more openly passionate. Although still tempered by a great amount of self-control, the quest is now after the sheer, inebriating pleasure of questing. Rather than presenting answers in careful doses, it is slowly becoming evident that, in the last period, the designers have been posing questions.

A similar pattern of progress may be observed in their other fields of design endeavor. In the case of furniture design, because of the nature of the production-distribution cycle, the emotional gesture must be a more measured one. It is not, after all, a throw-away item such as a piece of printed paper. But they have traveled from the carefully constructed structural feeling of the seating line “Saratoga” to a more humble acceptance of craftsmanship and manual uncertainty, substituting the round formality and warm textures of the “Acorn” chair for Saratoga’s precise geometry and immaculate skin. Thus again, the contingent is accepted and the unique instance tolerated, even welcomed. Wood and leather are chosen as instances of nature, and held together in ways that enhance their physicality. Gradually, the chimera of an eternal system crumbles, or at least lets its internal cracks come up to the surface. A readier acceptance of the temporary, of the accidental, of the one-of-a-kind, seems to emerge from this crisis, an acceptance which is all the more laudable if we perceive the existential turmoil these very gifted designers seem to be undergoing. I feel they are entering into a new, even more productive phase. With this exhibition they are taking inventory and evaluating the stock, populating the house they have built in foreign lands.

– Emilio Ambasz